As the month of Av begins next week, intensifying the three week mourning period Jews experience each year at the destruction of our civilization by Rome, the Women of the Wall (WoW) will likely hold their monthly Rosh Ḥodesh protest service at Jerusalem’s Kotel (Western Wall) plaza.

On the surface, WoW’s efforts are seen, especially by liberal Diaspora Jews, as fighting for the empowerment of women within Jewish spaces and challenging the monopoly of a single religious denomination when it comes to Jewish law and praxis in the State of Israel.

But when engaging either the issue of religious pluralism in Israel or the roles of women in Jewish life, especially at a time when we’re in the process of rebuilding Hebrew civilization after centuries of exile, there’s a danger in negligently applying Western paradigms to Jewish life.

– Jewish-Female Cognitive Dissonance –

Most of us rarely consider the extent to which Jewish women have sacrificed several aspects of our authentic identities. In the course of my experiences teaching young women, I’ve discovered that the values that many students see as defining strong female Biblical heroines are radically different from the values they have been conditioned to believe define strong women today.

In what appears to be an astounding display of cognitive dissonance, contemporary Jewish women often apply the underlying values of classical Western feminism to their roles in Jewish life at the expense of authentic Hebrew values, without ever addressing the tension between their Jewish and female identities.

Bourgeois Western feminism doesn’t necessarily work for all peoples and shouldn’t be imposed on women from cultures and with experiences that have little to do with the unique struggles of otherwise privileged white women in 20th/21st century contexts of North America and Europe. Doing so can quickly become a form of cultural imperialism, whereby the white woman savior complex employed to “liberate” oppressed women in the global periphery is actually used as an excuse to westernize indigenous peoples – especially when this “liberation” excludes and even silences the voices of the very women it claims to empower.

– Construction of Modern Jewish Identity –

Part of the confusion when it comes to applying the above logic to Jewish issues stems from the fact that our colonization in Western societies in recent centuries led many Jews to identify as a religious group. As part of the European Enlightenment and rise of nationalism, Jews were offered civil rights and inclusion into Western European states in exchange for discarding the ethno-national and territorial components of our identity.

Since the late 18th Century, a powerful assimilationist movement, especially among Ashkenazi Jews, has championed the abandonment of basic aspects of our identity in the hopes of gaining acceptance from host nations.

Moses Mendelssohn, father of the Haskalah, transformed the ethno-national “Children of Israel” that largely self-identified as a refugee population yearning to return to Palestine into European adherents of a religion called “Judaism” in an effort to prove loyalty and inculcate a sense of belonging to the nations in which Jews lived.

Once Jews in Europe began self-identifying as part of a religion, it was only a matter of time until many started imitating their Christian neighbors by factionalizing into denominations, the very existence of which should be understood as the christianization of Jewish identity. The founders of both Reform and Orthodox Judaism – Abraham Geiger and Rav Shimshon Raphael Hirsch, respectively – hoped that by destroying (Geiger) or severely softening (Hirsch) the ethno-national and territorial components of Jewish identity, we would succeed at proving our loyalty to, and gaining full acceptance from, European nation-states.

While this attempt may have ultimately failed disastrously in Europe, it has largely dominated Jewish communal thinking in North America, leading powerful Diaspora institutions to invest incredible resources into promoting their colonized “progressive” understandings of Jewish identity and practice onto the State of Israel.

– Feminism as Cultural Imperialism –

But there is nothing progressive about pushing Western values on an ancient culture that finds those values alien and threatening to its way of life. Diaspora Jews need to stop trying to “fix primitive Israelis” and start accepting the fact that we’re not going to adopt the Reform movement’s conceptions of Jewish identity.

My colleague Leah Nesya puts it best when she argues that because the Reform movement was primarily created for the purpose of allowing Jews in foreign lands (i.e. Germany, the United States, etc.) to better fit in with the host populations and cultures of those lands, while maintaining some form of watered-down Jewish identity, it makes no sense for such a movement to assert itself in a country where the host culture is actually Jewish.

Hebrew women have been living and conducting ourselves a certain way for thousands of years and we shouldn’t be made to feel insecure or apologetic whenever our rich and consistent nearly 4,000-year-old culture seems out of step with the transient politically correct fads of the West.

What has been cleverly marketed as a struggle over “religious freedom” at the Kotel is actually a well-funded effort to erode an indigenous people’s ancient way of life – a major front in a much broader culture war against the State of Israel’s organic Jewish character. Viewing this within the context of Jewish history reminds us that many of our people’s most violent conflicts have actually resulted from foreign powers and westernized Jews challenging Israel’s ancient folk ways.

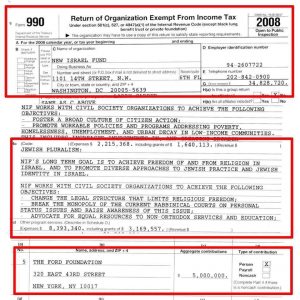

Heavily funded efforts by foreign organizations like the Ford Foundation, the New Israel Fund, and the Reform movement’s Religious Action Center to westernize Israeli society and dilute its native Hebrew identity attempt to misrepresent popular Israeli opposition to their efforts as a mere pack of Ḥaredi politicians undemocratically monopolizing control over a holy site belonging to all Jews, despite the fact that most Israelis oppose what we see as strange and offensive mock Jewish practices at our most sacred places.

– The Correct Address for Feminist Issues in Jewish Society –

This is not to say that real women’s issues don’t need to be addressed in Hebrew society. The aguna crisis begs for a solution. The shiddukh crisis and pre-marital relationships psychologically afflict Jewish women. Even problems as seemingly small as discomfort with a mikva lady’s job as it relates to a niddah causes many women real distress each month. And many women do search for meaningful ways to assert themselves in Jewish society. But applying foreign solutions to uniquely Hebrew problems can ultimately create far more social and cultural damage than the problems themselves.

The solutions presented thus far to all of the above-mentioned challenges have originated from westernizing forces and compromise ancient fundamental Hebrew understandings of marriage, the neshama, tahara, and tzniut – all concepts that strongly influence Jewish thought, praxis, and worldview. Pushing feminist solutions that force Jewish women to choose between fixing an injustice against them as women and protecting their value system and cultural sensibilities as Jews is not feminist. In fact, it places Jewish women in a miserable Catch-22, and in choosing to uphold our people’s way-of-life and value system, at best we are left without recourse to improve our conditions or overcome the very real struggles we face as women in Hebrew society. At worst, we become the epicenter of a social backlash against cultural imperialism, whereby even discussing our problems becomes taboo.

Rather, Diaspora Jews concerned with the status of women in Israeli society would do well to entertain a Transnational feminist paradigm and participate in creating a uniquely Hebrew feminism that addresses the needs of Jewish women within the context of our people’s historic values, native culture, unique struggles, and identity. This process must begin with finding out from Hebrew women ourselves how we can best be empowered, so we can fully participate in rebuilding our people’s civilization in a manner that expresses our holistic identities without compromise or concession.