The Catholic Church recognizes at least three different martyred saints named Valentine (Valentinus). One story suggests Valentine to have been a third century priest who continued to perform marriages for soldiers in secret after Emperor Claudius II outlawed marriage for these young men altogether.

Another suggests that Valentine may have been killed for his attempt to help Christians escape Roman prisons and, when imprisoned himself, fell in love with a young girl to whom he allegedly wrote letters signed “From your Valentine” – a valediction still used to this day.

Although the factualness behind the Valentine legends is murky at best, the stories emphasize a heroic, romantic and salvific conception of love.

While some argue that Valentine’s Day is celebrated on February 14 to commemorate the anniversary of Valentine’s death or burial — which likely occurred around the year 270 — others posit that the Christian Church strategically chose to place St. Valentine’s feast day in the middle of February in an effort to Christianize the pagan celebration of Lupercalia, a fertility festival dedicated to Faunus, the Roman god of agriculture.

Lupercalia, which took place on February 15, was outlawed by Pope Gelasius at the end of the fifth century for being “unchristian” and replaced with St. Valentine’s Day on February 14.

The evolution of St. Valentine’s Day into a romantic holiday began in fourteenth century England, when the tradition of courtly love based on chivalry and nobility flourished.

For many Jews it became a day of mourning after the February 14, 1349 Strasbourg massacre, when several hundred Jews were publicly burnt to death, and the rest of them expelled from the city as part of the Black Death persecutions. It was one of the first and worst pogroms in pre-modern history.

By the eighteenth century, the day had grown into an occasion in which couples expressed their love for each other by presenting flowers, offering confectionery and sending greeting cards.

In contemporary times, Valentine’s Day has largely been stripped of its commemorative Christian significance and replaced with the more contemporary religious impulse toward consumerism and mass consumption.

In a contemporary post-Christian West, where worshipping the individual Jesus has largely been replaced with worshipping the individual self, Valentine’s Day is one of the most poignant depictions of how a religious commemoration of divine service marked by martyrdom has become a religious commemoration of self service marked by consumerism. Westerners have not actually become less religious — now, however, they simply worship themselves.

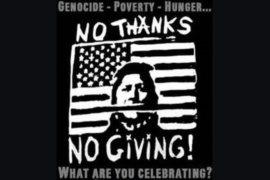

For all its historical and contemporary purposes, Valentine’s Day flies in stark contrast with the Jewish value system. Valentine’s Day represents a global trend from Christianization to Westernization, both frameworks Jews have throughout history sacrificed their lives and livelihoods to reject.

Hebrew civilization has always rejected and continues to reject the Christian and post-Christian ethos of worshipping the individual, be it Jesus or the self (a whole piece can be written about how the salvific aspects of Jesus would naturally lend themselves to a culture that sacrificed collective good for staunch individualism, but we can save that discussion for another day).

The Jewish holiday of love, Tu B’Av, when juxtaposed with (St.) Valentine’s Day, highlights a truth that is often cumbersome for many Jews to accept — that the contemporary West is actually not founded on Hebrew principles or doctrine.

Tu B’Av takes place on the 15th day of Av and is both an ancient and modern holiday. Originally a Biblical-era day of joy, Tu B’Av marked the beginning of the grape harvest. Interestingly, Yom Kippur marked the end of the grape harvest, and on both dates the unmarried girls of Jerusalem dressed in white garments and went out to dance in the vineyards (Ta’anit 30b-31a). The same Talmudic section states that there were no holy days as joyous for the Jewish people as Tu B’Av and Yom Kippur.

Various reasons for celebrating Tu B’Av are cited by the Talmud, including that while the Hebrew tribes wandered the desert for forty years, female orphans without brothers could only marry within their tribe to prevent their father’s inherited territory in the Land of Israel from passing on to other tribes. On the fifteenth of Av, this ban was lifted and inter-tribal marriage was allowed.

Talmudic commentators also posit that on this date King Hoshea of the northern Israelite kingdom removed the sentries on the road leading to Jerusalem, allowing his subjects to once again make pilgrimage to the Jerusalem Temple. Additionally, the date marks when the Roman occupiers permitted burial for Bar Kokhba’s fallen warriors massacred at Betar.

In more modern times, Tu B’Av marks an emotional “high” to counter the “low” of the three week period of mourning commemorating the destruction of the first and second Temples. In some ways, the founding principles of Tu B’Av serve as a microcosm for what Hebrew civilization holds important — the ritualization of collective memory, the symbiotic bond between a land and its people, as well as the synergistic coupling of sexual and spiritual purity. In short, sanctifying the land and people expressed holiness in order to mirror His holiness.

In contemporary Israeli society, Tu B’Av has become a romantic Jewish holiday more closely related to Valentine’s Day than our ancient roots. After millennia in exile, the erasure of Jewish identity was the direct result of a Christian and post-Christian steamroller that sought to erase cultural differences in order to homogenize outsiders and bring them into the fold.

On Tu B’Av in Israel, the entertainment and beauty industries work overtime and the stress on vanity, instant gratification and sexual promiscuity highlights a successful colonial project, where the slave still wishes to be like his master even after he attains freedom. This schism between the Western and Jewish cultural gap is profound in Israeli society, and it’s worth thinking long and hard about which side of the divide is truly free.