The Jerusalem Municipality is scheduled to vote this week on whether or not to allow the First Station – a popular venue with shops, restaurants, and public events – to remain open on Shabbat. All over social media, Jerusalemites from diverse backgrounds have been crying out against this initiative, claiming that it’s kfiyya datit (coerced religiosity) and that the city belongs not only to Torah-observant Jews but to all Jews (and even non-Jews).

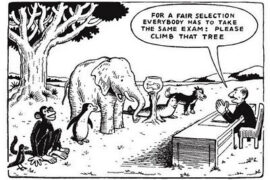

Anyone who lives in Israel or is familiar with our socio-political divides knows that this argument isn’t new. For years, people from all across the spectrum have been trying to decide if buses should run and stores should open on Shabbat. The typical argument against is that Israel is a Jewish state and Shabbat should be respected in the public sphere. The general argument in favor is that not everyone observes Shabbat according to the Jewish people’s ancient laws, and that those who don’t have lives they want to live, even on Saturday (Israel’s single weekly day off). These arguments more or less prioritize the rights of individuals to choose how they’d like to enjoy their day off.

But having buses running and shops open on Shabbat has significance beyond the personal freedoms of individuals – it’s an issue of social justice.

As nice as it would feel to be able to ride the bus to the beach on your day off rather than pay the extra money to rent a car for the weekend, public transportation comes at the expense of the bus driver’s ability to take the day off. Going to a restaurant on a Friday night is fun, but what about the waiters who don’t get to be with friends or family Friday night because they’re serving you instead?

A Jewish state needn’t coerce behavior but it should pursue policies that express our people’s values. Hebrew civilization introduced the concept of Shabbat into the world at a time when people literally worked their slaves to death. The concept revolutionized how mankind relates to workers’ rights. In the modern Jewish state, no one is trying to force anyone else to attend Synagogue or recite kiddush, but everyone – including workers employed at Jerusalem’s First Station – is entitled to a day of rest.

When people complain about how inconvenient it is that they can’t ride buses or go out on Shabbat, all I hear is that they think their own leisure and convenience is more important than acceptable conditions for workers with low-wage jobs.

The response to this might be: “Well, maybe the people who work on Shabbat need the extra money, and who are we to deny them the opportunity to make more?”

I have a few ways of responding to this logic.

- The most obvious answer is simply to pay people living wages. The minimum wage in Israel is abominably low. If this is an issue you truly care about, fight for a higher minimum wage (and maybe use the cash you would’ve otherwise used for a meal at a restaurant Friday night to give your waiter a bigger tip on Thursday).

- This logic can lead to jobs being denied to Jews who either celebrate Shabbat in the traditional sense or who want to use it to spend time with their families. When hiring, employers take a worker’s availability into consideration. So those who prefer not to work on Shabbat for whatever reason might have a harder time finding jobs.

- Along a similar vein, those who do find employment might feel uncomfortable saying that they’re not willing to work on Shabbat for fear of losing their jobs to those who are – this is actual coercion as it essentially restricts a worker’s freedom to decide when to work.

Shutting down shopping centers and public transportation on Saturdays doesn’t coerce Israelis into observing Shabbat. But opening them would actually coerce workers and limit their decision making power. Respecting Shabbat in the public sphere protects workers’ rights and levels the playing field so that on at least one day a week, the CEO of a successful startup and a waitress working for less than minimum wage are equal. So until technology arrives at the point where we can have robots driving our buses, selling us clothing, and serving our food, we should prioritize Shabbat in the public sphere as an expression of our state’s Jewish identity – not in the sense that we should impose “religious observance” on the public but rather in the sense that we should prioritize the value of protecting workers’ rights over the rights of individuals to choose how they enjoy their day off.