Renowned medieval Hebrew poet and philosopher, Rabbi Yehuda HaLevi wrote, “The servants of time are the servants of servants; a servant of the Lord alone is free.”

This bold declaration is a direct challenge to the ideology that has driven Western civilization for millennia. By exploring its meaning, we can better understand the civilizational clash playing out in the streets of Israel over the issue of judicial reform.

What is a “servant of time?”

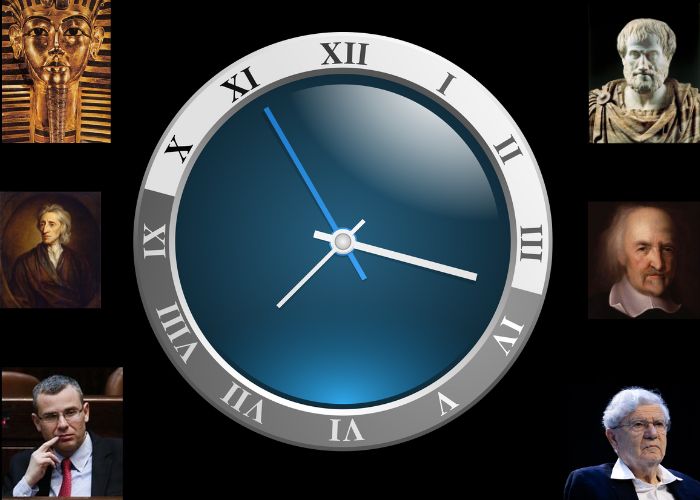

In the opening paragraphs of his book, The Kuzari, Rabbi Yehuda HaLevi presents an array of ideologies that dominated the intellectual and theological landscape of his time, depicting the fictionalized conversations of the king of Kuzar with an Aristotelian philosopher, a Christian priest, and a Muslim imam before arriving at “the despised faith” as he meets a rabbi, who dominates the rest of the book.

One of the sharpest contradictions in these paragraphs between the philosopher and his peers is his approach to time. As a result of his assertion that the world is eternal, and not created, he posits that time has always been and will always be – that it has no end and no beginning. In essence, he deifies time.

As the rabbi methodically challenges the ideological paradigm of the king, he dispossesses him of the notion that the philosophers came to this conclusion objectively – since the human intellect, which necessarily operates within the bounds of time, is incapable of assessing a reality that “precedes” time.

It becomes clear that unlike Socrates, who recognized the limits of the human intellect, Aristotle and his students were influenced by their subjectivity in asserting the eternality of the world. Consciously or unconsciously, their assertion that time is eternal serves as a justification for their ideological paradigm. This clarification brings into focus the moral implications of such an approach.

In the philosopher’s introduction, his cosmology and his theology are necessarily linked. Just as there is no Creator, and time is limitless and absolute, there is no Divine Will, and human nature is limitless and absolute.

Therefore he asserts, “you need not concern yourself with which dogma, religion, action, speech, or language you practice; you may even make up your own religion… or accept the rational ethics of the philosophers.”

In other words, follow your heart’s desire, because it doesn’t matter. If time and nature are absolute, not only is choice irrelevant, it is impossible. The philosopher himself implies that all phenomena – which necessarily include human behavior – are the eternal, inescapable, natural progressions of cosmological processes.

So what is a “servant of time?” Someone so enslaved to their belief in the strength of human nature and desire that they see no recourse but to justify that desire whenever possible, and to suppress it by force when it is perceived to be beyond the pale of societal acceptability and thus dangerous to one’s self.

The philosopher’s cosmology has been sufficiently debunked today, and no serious “man of science” would claim that the earth and humanity have always existed. Albert Einstein, when asked to define time, bitingly quipped, “time is what a clock measures.” And his theory of relativity radically reshaped our understanding of the supposed absoluteness of time. Yet despite all this, the philosopher’s conclusions have not been abandoned.

While the philosophers of Rabbi Yehuda HaLevi’s age may have understood a beginning to the world to necessitate an active Creator, later thinkers have followed in his path of creating rational justifications and “proofs” for the absence of an imminent Divine, regardless of the human incapacity to objectively assess the matter. Therefore the idea of inescapable human nature remains alive and well as the central pillar of liberal humanism, which animates prevalent conceptions of democracy, not just as the will of the majority, but as a set of values and norms that demarcate the line between civility and barbarity.

John Locke develops this theme in his Second Treatise on Government, where he writes, “To properly understand political power and trace its origins, we must consider the state that all people are in naturally. That is a state of perfect freedom of acting and disposing of their own possessions and persons as they think fit within the bounds of the law of nature.”

The “free” man in the state of nature only agrees to submit his freedom to an authority out of fear that someone else’s freedom poses an existential threat to his own freedom. Therefore, such a government must simultaneously limit threats to personal freedom to do as one pleases, while maximizing that same freedom.

Thomas Hobbes is even more explicit in Leviathan.

“Life is but a motion of limbs. For what is the heart, but a spring; and the nerves, but so many strings; and the joints, but so many wheels, giving motion to the whole body,” he writes, taking up the aforementioned philosophical thread that human action is simply the product of material causes – biology and chemistry and physics – that determine his choices.

This necessarily leads to a state of “war of all against all” in Hobbes’s conception, which can only be averted by the state, a monstrous center of power, which can restrain human behavior by force, and which the majority consents to based on the individuals’ inescapable natural desire for self-preservation and growth.

From the Classical and Medieval philosophers to the Renaissance and Enlightenment minds behind modern state institutions, there is universal agreement on one point – man is an animal, driven by his inescapable desires, and the only recourse is to force his hand in order to protect each individual from his carnivorous neighbors.

But are we so cynical? Is man truly a servant of time, a slave to his base desires?

Israel’s Torah has a different answer. Time is not eternal, nor is human nature inescapable. Man was created with free will, the ability to choose between good and evil. John Steinbeck succinctly distilled it down to a single phrase, “thou mayest” – you have the ability to overcome your natural instinct to do wrong.

When our written Torah commands “do not murder” and our oral Torah delineates the boundaries of this prohibition, it is a clear affirmation of the human capacity to choose not to murder – even when his instincts demand it and his intellect may justify it.

This is a serious departure from the “social contract.” Man mustn’t murder, not because he fears the consequences that his society established for such behavior, but because he chooses to live as a manifestation of the will of his Creator, as a being capable of not killing.

Therefore, the Torah commands Israel to sanctify time, through Shabbat and the festivals. This is not simply a day of rest, or a commemoration of a major event in the nation’s history. Rather, as the Ramban explains in his commentary at the end of Parshat Bo, it is a philosophical statement, affirming creation, revelation, and choice – as a rejection of the slavery to time that the Egyptian empire represented that has been passed down to the political ideologies of our day and age.

This central paradigm shift is critical for understanding our political reality, and to imagining a way forward. If human nature is not fixed on self-destruction, but rather has the potential to choose which way it will go, the state is no longer the only avenue for productive society.

While even the rabbis saw the importance of the state in responding to destructive behaviors (see Avot 3:2), this deterrence is necessitated by the reality of choice – and that some will choose evil – rather than by an inescapable inclination towards destructive self-interest. Therefore, the state need not be an overbearing, punitive, Hobbesian Leviathan, but rather a system of restorative justice, that can address the harm done by those who choose evil, and prevent their corruption from spreading.

Even more critical are the implications of this paradigm shift for education.

Educating on the basis of human nature has a major pitfall – in anything that the state cannot see, anytime someone believes they can’t be caught, deterrence crumbles and unbridled desires take their toll. But if we educate towards personal responsibility to choose, not “or else,” but as an expression of our humanity and our gift of freedom, we can create a generation like the prophet Yirmiyahu envisioned, “no longer will man say to his neighbor and will man say to his brother, ‘heed HaShem,’ for they will know me, from the least of them to the greatest of them.”

This is true freedom – choosing to do what is right out of knowledge, out of an internalized identification with its justness. “Knowing” the Divine and not simply restraining one’s basest impulses out of fear. Imagine how different the heated debates around Torah and state in Israeli society would be if all parties across the political spectrum agreed upon this definition of freedom.

But alas, Israeli society is sharply divided, between those who see government as Locke and Hobbes did, an instrument to maximize personal freedoms by disincentivizing certain parts of human nature, and those who recognize a Source beyond socially contracted morality to determine right from wrong.

The split does not cleanly divide between the government and the opposition – some of the figures advancing judicial reform legislation today agree with Locke and Hobbes on principle, and only seek to strengthen the role that the majority’s consent plays in determining the limits of the Leviathan’s power. But a rising tide in Israeli society wholeheartedly rejects the premise that morality begins and ends at the bounds of human intellect.

As this segment of the population gradually takes power in more of Israel’s state institutions, the question of education will be essential. Will we see the “theocracy” that the opposition today so deeply fears? Will the Leviathan be repurposed to transform the servants of time into slaves of halakha? Or will a conscious connection to our Divine Source be free, not through coercion but through educating our children about personal responsibility and the true meaning of choice?

As in all things, the answer is, “thou mayest.”