Why does Israel sound so harsh in his final blessings to his three eldest sons?

What makes Yehuda the only son of Israel properly suited for national leadership?

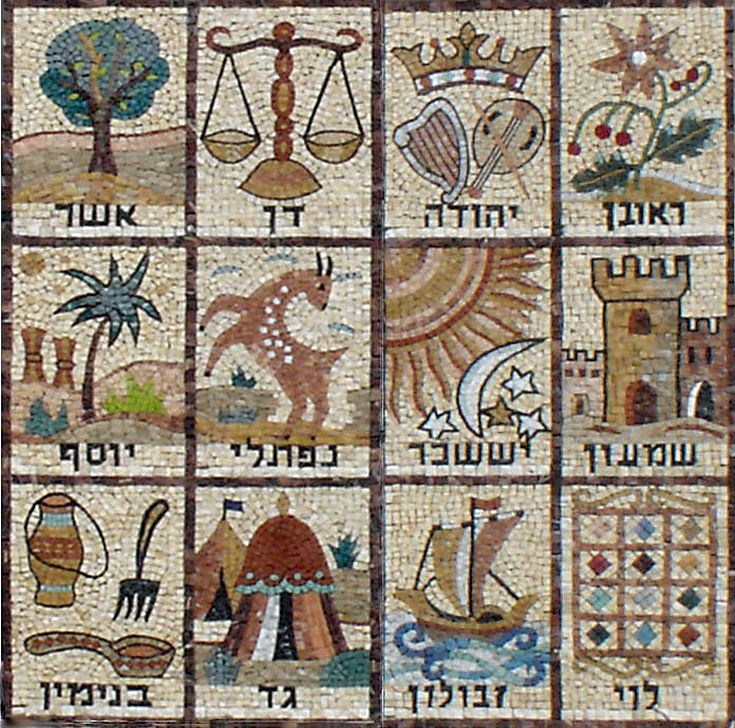

In what way were each of Yaakov’s sons unique prototypes for different kinds of Jews throughout history?

For more content from VISION Magazine, subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on Twitter @VISION_Mag_, Facebook and YouTube. If you haven’t already, don’t forget to subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud, iTunes, Stitcher, TuneIn, or Spotify and leave a rating and review to help us get our message out to a wider audience!

To support the podcast, head over to our PayPal portal and be sure to write a note that your contribution is for the podcast.

Hosted by: Yehuda HaKohen

Transcript:

Parshat Vayeḥi begins seventeen years after Yaakov’s family arrived in Egypt. During those years, the famine had ended and many of Yosef’s radical reforms had been institutionalized. Yet following his successful management of the crisis, Yosef had become less indispensable to the regime and appears in this parsha to be far less powerful or important in Pharaoh’s court than in previous parshiot.

As Yaakov, at the age of 147, realized that he would soon leave the world, he took action to ensure the proper developmental trajectory for his family.

The first step was to have Yosef swear that he would bring Yaakov’s body to Hebron to be buried in the cave of Makhpela alongside Avraham, Sarah, Yitzḥak, Rivka and Leah.

The Midrash notes that a solemn oath was necessary for a number of reasons, most notably that it gave Yosef the moral strength necessary for its fulfillment and that it would help Yosef convince Pharaoh to allow and even facilitate its execution. When later seeking permission from the monarch in B’reishit 50, verse 5, Yosef would in fact mention that his father made him swear an oath to burry him in Hebron.

Yaakov’s insistence that Yosef burry him in Hebron might also have been meant as a way to correct Yosef’s approach to achieving Israel’s national mission. In our episode on Parshat Vayigash, we saw how Yosef had actively pushed for the Hebrew clan to relocate to Egypt but live separately in Goshen so as to maintain their unique identity. This should be understood as part of a plan that sought to make Israel’s family the priests of HaShem and conductors of Divine light within the kingdom of Egypt in order to influence the powerful kingdom and transform it into a light unto nations. This plan would be a hybrid of Israel’s path with that of Naḥor.

But now, after seventeen years, it was clear that this plan hadn’t worked and that Hebrew influence on Egyptian society had become weaker since the end of the famine. In demanding that Yosef return his body to Hebron, Yaakov wanted to make clear his opposition to this approach and to shatter the illusion of Yosef’s erroneous fantasy.

The second step Yaakov took to prepare for his departure from our world was to offer unique brakhot to each of his sons – the heads of the Hebrew tribes.

These brakhot had two unique purposes. One was to clarify each tribe’s strengths, weaknesses and proper place within the Israeli national collective. And the second was to clearly determine which tribe should lead.

Before addressing the others, Yaakov summoned Yosef to come to him with his sons Menashe and Ephraim. B’reishit 48, verse 2, tells us that “Israel summoned his strength and sat up in bed,” meaning that Yaakov exerted himself to become Yisrael in order that Menashe and Ephraim would receive their brakhot from the gadlut – greatness – form of his attribute of tiferet.

In verse 4, Israel deliberately informed Yosef that the Creator connected his promise to him with possession of the land in order to communicate the need to ultimately return to it. Then in verse 5, the Hebrew patriarch stated that the two sons born to Yosef in Egypt in isolation from the rest of the clan would be elevated to the level of being like Yaakov’s own sons. Menashe and Ephraim were at this point raised to the status of full fledged tribes, which meant that Yosef was receiving the double portion inheritance entitled to a firstborn and also being elevated himself to a status somewhere between the patriarchs and tribal heads.

As he was about to offer brakhot to Menashe and Ephraim, Israel strangely asked Yosef in verse 8 “mi ele” – “Who are these?”

Israel wasn’t having a senior moment. He obviously knew who his grandsons were. In fact, he had just named them in verse 5. The point of this question here in verse 8 was to ask Yosef to tell him something about his sons. And Yosef answers in verse 9 that “They are my sons whom the Creator has given me here.”

By including the word here, Yosef responded with what he considered to be most significant about his sons – that they had been born in Egypt. Not only had they been born in Egypt but also at a time when Yosef suspected his father of complicity in what his brothers had done to him. Therefore, the brakhot Israel would give his grandsons would need to fully reunite them with the clan and correct the deficiency in the ideas Yosef had raised them with. Although Yosef had brought his sons before Israel so that his father’s right hand would be on the elder Menashe and his left hand on the younger Ephraim, Israel crossed his arms and reversed the order of seniority, which on a deeper level was meant to correct Yosef.

The purpose of Israel’s reversing the order of seniority is relevant to the names Yosef had given them when they were born. The name Menashe was meant to say that the Creator had helped him forget – from the Hebrew root letters nun–shin–hei – the hardships of life in his father’s house. The name Ephraim meant that the Creator had made him fruitful and successful in his new life.

When naming his sons, Yosef had expressed that he owed his success to having been able to forget his difficult past. At that time, he might have seen the key to success as completely forgetting his past. The message Israel was sending Yosef by switching the order was that one shouldn’t forget his entire past in order to succeed. Rather, success can allow one to forget, or at least feel less pain from, less important aspects of the past.

Israel’s brakha will cause Menashe to becomes a symbol not of forgetting but of remembering. The fact that Menashe understood what it meant to forget allowed him to appreciate the full value of memory. Centuries later, Menashe would be the only tribe to receive territory on both sides of the Jordan River, essentially linking Transjordan with Eretz Canaan. By spreading across both banks, Menashe would become a unifying link that would keep the Hebrew tribes connected as a nation.

It’s also important to note that the tribe of Ephraim, which now became the senior of Yosef’s sons, would later become the most zealous of the tribes in trying to correct Yosef’s Diasporic orientation. The Midrash teaches that during the period of Israel’s slavery in Egypt – 30 years before our freedom – the tribe of Ephraim, under the leadership of a revolutionary named Nun, would initiate an escape that would ultimately bring them to fall in battle against the Philistines of Gat. But once Moshe came on the scene and began the process of our Exodus, a son of Nun named Hoshea immediately joined Moshe’s cause and became his top student. Years later, in the desert, Moshe would change Hoshea’s name to Yehoshua. And following Moshe’s departure from our world, Yehoshua bin Nun would lead the Hebrew tribes in the liberation of our land.

Once finished blessing Ephraim and Menashe, Israel turned to Yosef. We see him saying to Yosef in B’reishet 48, verses 21 and 22 that the Creator “will be with you and will bring you back to the land of your fathers. And as for me, I have given you one portion more than your brothers, which I took from the hand of the Amori with my sword and with my bow.”

One way to read this is simply that Yosef received a double portion because he had attained the status of the firstborn.

But there are also other ways to understand this. The Hebrew text that I’m translating as “one portion more” actually reads “Shkhem aḥad,” which can either be understood as “one plot of land” or as “one city of Shkhem.”

Shkhem is where Yosef’s tomb will later be located and it sits exactly on the border between the territories of Ephraim and Menashe. Rather than divide the city between Yosef’s sons, Israel gave it to Yosef so that the entire city would belong to both tribes and unite them as one.

The part about Israel taking the city from the Amori with his sword and bow may not be a reference to Yaakov himself but to his sons Shimon and Levi, who conquered the city when they rescued their sister Dina. Although the Midrash does show that following the rescue of Dina and conquest of Shkhem, Yaakov’s family had to fight and overcome several other city states in the area. This was actually a six day war that Yaakov himself participated in. So it’s possible that Israel was referencing that.

But another way to understand this verse is that Israel was giving Yosef a brakha for military prowess, saying that “I give you an advantage, the ability to wrest land from the Amori with sword and bow.”

This is important because Yosef’s descendant Yehoshua bin Nun would later lead the nation in fighting for the land. Yehoshua would also lead Israel’s war against Amalek in the desert. Yosef is the part of Israel that can master the material world, be like Esav and ultimately defeat Esav. But until this point, we don’t see Yosef having any personal experience with war. So, according to this understanding, Israel gave Yosef a brakha for success in battle, which would be crucial both for his tribes and for the spiritual force of Yosef within Israel to be able to succeed.

Following this special brakha for Yosef and the elevation of Ephraim and Menashe, Yaakov then gathered his other sons together for the brakhot that he would bestow upon each of them. We’ve already mentioned that one of the purposes of these brakhot was to determine who should lead the nation. Because Israel’s leader must ultimately be the tribe of Yehuda, Yaakov’s words regarding his three eldest sons – those older than Yehuda – appear alarmingly harsh.

This is likely because it was important for Israel to ensure that there would be no rivalries for political leadership amongst the brothers. With the exception of Yosef – and perhaps also Binyamin – there was no real threat that any of the tribal heads younger than Yehuda would see themselves as national leaders. But older brothers could potentially feel resentful that Yehuda had usurped their rightful place in the national hierarchy. Therefore, Yaakov’s brakhot to his first three sons were meant to clarify that they weren’t properly suited to lead the nation.

Before giving each tribe its individual brakha, the patriarch said in B’reishit 49, verse 2, “Gather yourselves and listen, Oh sons of Yaakov, and listen to Israel your father.”

The Hebrews in exile, the sons of Yaakov, had to hear and accept the words of Israel, for only upon returning to their country would the brakhot of the tribes actually be realized. In fact, the entire point of these brakhot was to clarify the individual place and function of each tribe within the Israeli national collective and to avoid conflicts between those who might not have on their own realized their rightful and most productive place within the national formation that would later be established.

The first brakha went to Reuven. As the firstborn, Reuven enjoyed the greatest potential for leadership, but his impetuous behavior showed a lack of forethought. A national leader needs to be prudent and judicious because governments can’t make hasty decisions without weighing the consequences of those decisions.

B’reishit 49, Verse 4 states that Reuven mounted his father’s bed and disgraced him by ascending his couch. Chapter 35, verse 22 states that “While Israel dwelt in that land, Reuven went and lay with Bilha, his father’s concubine, and Israel heard. And the sons of Yaakov were twelve.”

Reuven’s offense was actually not as serious as the pshat – the surface level reading of the Torah text – seems to suggest. The statement that he “lay with Bilha” is followed immediately, in the very same verse and without interruption, by the words “And the sons of Yaakov were twelve,” emphasizing that Reuven was not excluded from the family or from the list of Hebrew tribes.

This means that his crime couldn’t have been as serious as a straightforward reading of the text would suggest.

Our Sages teach that Reuven didn’t actually have intimate relations with Bilha, but merely rearranged Yaakov’s bed, and lay down where it was inappropriate for a son to lay down. Our Sages explain that while Raḥel was alive, Yaakov’s personal bed was in Raḥel’s tent. Leah and her sons for the most part respected the established family hierarchy, according to which Raḥel was recognized as Yaakov’s primary wife.

But after Raḥel’s death, Yaakov transferred his bed to Bilha’s tent instead of moving it to the tent of Leah. Bilha had been Raḥel’s servant and moving his bed to her tent might’ve been a way of Yaakov expressing that the memory of Raḥel was more precious to him than his living wife Leah.

As Leah’s eldest child, Reuven was obviously sensitive to his mother’s honor and feelings, so it makes sense that he would have been outraged by what he likely saw as his father humiliating his mother. He impulsively rearranged his father’s bed by moving it from Bilha’s tent to Leah’s. Reuven may have meant well but because he dared to interfere in his father’s intimate relations with his wives – something that’s absolutely none of a son’s business – the Torah harshly accuses him of having committed adultery. But he didn’t actually commit adultery.

After learning of what Reuven had done, the verse states that Yaakov reacted as Israel, meaning that he reacted as required by the laws of political authority. Reuven retained his position as one of the Hebrew tribes, which might not have been the case had he actually been intimate with Bilha, but he did lose his firstborn status because responsible leadership requires a cool head and even temper. People who can’t control their emotions or restrain their impulses, even if they’re good hearted and inherently righteous like Reuven, shouldn’t be trusted with political power.

Reuven was divested of the rights of the firstborn – the kingship, the priesthood and a double share in his father’s inheritance, which were then divided amongst Yehuda, Levi and Yosef respectively.

Next, Israel addressed Shimon and Levi, relating to them in B’reishit 49, verse 5, as a pair of brothers, whose weapons are tools of lawlessness. It’s not fully clear from the text if Israel was referring to their war on the city of Shkhem, when they rescued Dina, or to their attempt to kill Yosef before Reuven stopped them. If we understand Israel’s brakha to Yosef in chapter 48, verse 22, as referring to the conquest of Shkhem, it’s unlikely that it’d be that.

In any case, Israel acknowledged Shimon and Levi to be great warriors but also somewhat rash and thoughtless in the application of their talents. Shimon and Levi were fanatics and their spiritual forces within Israel’s collective identity essentially represent something similar to Yehuda but in more extreme form.

We already discussed in a number of previous episodes that Yehuda represents that part of Israel’s identity that sets us apart from other peoples and is uniquely special to us. Our Torah, our country, our culture, our values. While expressions of the force of Yosef might generally understand the world through the lens of what’s politically correct internationally, Jews who express the force of Yehuda tend to live in the psychological paradigm of Jewish history. Shimon and Levi are the extreme expressions of that.

To a certain extent, this extremism has its place and can be productive when properly channeled. A nation should have a certain number of fanatics, but too much fanaticism can make it impossible to maintain stability. Because a fanatic can generally only see any given situation from their own point of view, they generally have trouble entertaining opinions other than their own.

So in verse 7, we see that Shimon and Levi should be divided in Yaakov and scattered within Israel. The benefits that Shimon and Levi can bring to the collective nation are realized only when they are separated from each other and scattered amongst all the other Hebrew tribes.

The tribe of Shimon received its portion of land inside the tribal territory of Yehuda, which would allow it to maintain its role as the extremist element within the force of Yehuda. Our Sages teach that as a reward for Shimon rescuing Dina from Shkhem, his tribe was primarily responsible for early childhood education. Fanatics happen to be good teachers of children because children often need black and white values and very clear moral messages. Us good, them bad. You touch my sister, I slaughter your village. Only when children become older can they properly receive and understand more nuanced approaches to difficult issues.

The tribe of Levi, however, would be settled across different cities throughout the country and would for the most part come into contact with all the Hebrew tribes.

The kohanim, the priestly sub tribe of Levi, would essentially be responsible for enhancing the nation’s spiritual experience and connection to HaShem. Levi wouldn’t be landed and therefore had little to do with agricultural endeavors. The other tribes would help support them while the Leviim and kohanim focused on teaching Torah and on their work in the Temple.

The placement of intense tribes like Shimon and Levi in relation to the larger nation should be understood similarly to salt and pepper in relation to food. They’re crucial for the overall wellbeing of the nation, but only in limited quantities, and when dispersed among the rest of the tribes.

Next on the list was Yehuda. Verse 8 states that Yehuda’s father’s sons would bow to him. He’s immediately distinguished in that all of his brothers would consent to his reign. Without this consent, his political leadership wouldn’t be possible.

Verse 9 calls Yehuda a lion cub growing on his prey. And that he crouches down like a lion. The crouching down should be understood as having patience, which provides the tribe of Yehuda’s actions with a very solid foundation.

And the Midrash understands lion cub not as young lion but rather as a cub who becomes a lion. Yehuda’s main power was his ability to grow and to correct himself, expressed through the metaphor of a cub advancing to become a lion. Yehuda’s ability to acknowledge his own shortcomings and to improve himself is a critical prerequisite for the leader of a nation.

Verse 10 states that the scepter shall not depart from Yehuda – from the time David ben Yishai took the kingship, it would belong to the tribe of Yehuda forever.

And verse 12 states that Yehuda’s eyes are darker than wine and that his teeth are whiter than milk. The red of wine represents the quality of g’vura – justice or restraint – while the white of milk represents the quality of ḥesed – kindness or giving. The kingdom is only able to stand firm when justice and mercy are properly united. Because his authority will be acknowledged by his brother tribes, Yehuda will be able to calmly and confidently makes national policy decisions. Yehuda’s strength lies not in suppressing others but in constantly trying to improve himself. It therefore makes sense that leadership should belong to him.

Unlike Yehuda, the other tribes weren’t able to create lasting kingdoms, because each of them was too narrowly focused on their individual concerns to the detriment of other aspects of life. Therefore only Yehuda, who was broadminded but focused inward, was fit to become leader of the nation as a whole.

Israel then moved on to Leah’s younger sons. Z’vulun was from a certain perspective the opposite of Shimon and Levi. The tribe of Z’vulun’s main occupations would be fishing and international trade. In contrast to Shimon and Levi, who were inclined towards zealotry and for the most part only circulated among other Hebrews, Z’vulun would come into contact with many peoples and cultures.

Their seafaring adventures would bring them into business relationships with all sorts of people. Z’vulun would therefore be the most cosmopolitan of Leah’s sons and have a very broad worldview.

Although Z’vulun was younger than Yissakhar, he received his brakha first. This was because Z’vulun would support Yissakhar’s study of Torah.

By mutual agreement, Z’vulun would provide for both tribes’ combined material needs and Yissakhar would learn Torah for both tribes.

Although Yissakhar would become strong in Torah and many of its tribesmen would serve on Israel’s high court, the tribe was generally unfit for national leadership because it tended to prefer the quiet life of learning and teaching Torah and had no real interest in commerce or statecraft.

But the potential danger in making Torah study one’s sole occupation while material and security needs are provided by others is that it could lead one to the conclusion that there’s actually no need for Israel to have political independence. Relating to the management of a nation as a useless burden could cause a person to avoid political responsibility. While the Torah – the prophetic Divine Ideal from before Creation lowered into our world for the sake of elevating it to its highest potential – is our soulmate, that Torah itself instructs the Children of Israel to establish political sovereignty in a very specific territory in order to fulfill the Hebrew mission in history.

After the sons of Leah, Israel moves on to the eldest son of Bilha. Verse 16 states that Dan will govern his people, as one of the tribes of Israel. The tribe of Dan to a certain extent considered itself separate from the national collective. The tribe would actually become so disorganized that it wouldn’t be able to manage its initial allotment of land, which would cause it to relocate from what we today call Gush Dan to the north of our country.

Just as Shimon can be seen as an extreme expression of Yehuda, Dan should be understood as an extreme expression of Yosef. While Yosef can’t be satisfied with Jewish particularism and therefore seeks out a relationship with the rest of humanity, Dan has a tendency to go even further in this direction.

Verse 17 refers to Dan as a serpent by the road that bites the horse’s heels so that its rider is thrown backwards. This tactic of surprise attack is characteristic not of a soldier but of a guerrilla. A clear example of such a man from the tribe of Dan will be Shimshon, who would battle against the Philistines not as part of a regular army but as a lone partisan. The tribe of Dan is anarchist in nature and has trouble submitting to authority.

Verse 18 shows our patriarch beseech HaShem that the tribe as Dan should not be completely severed from the nation of Israel.

Israel’s identity consists of two opposite poles – the tribe of Yehuda, representing malkhut – royalty and statehood – and the tribe of Dan, representing anarchy and an impulse to exceed the limitations of the system.

It’s noteworthy to mention that when it came time to build the Mishkan in the desert, HaShem would select two engineer-architects. Betzalel ben Uri of the tribe of Yehuda and Oholiav ben Aḥisamakh of the tribe of Dan. Creating the Mishkan would require a synthesis of these two opposite forces.

The next son of Israel to receive its brakha would be Gad son of Zilpa. Of all the Hebrew tribes, Gad would produce the fiercest warriors and many would serve as commanders in Israel’s army.

Gad’s tribal territory would be on the northern Gilad on the east bank of the Jordan. But when it came time to conquer the land under Yehoshua bin Nun, Gad’s warriors marched in the front.

The tribe actually had a unique fighting style. The Hebrews in ancient times would fight using sickle swords, similar to the Egyptians, and the tribesmen of Gad were known to use their sickle swords in such a way that would take off an enemy’s head and right arm in one strike.

One of my sons recently pointed out to me that Yehuda Maccabi, although a kohen from the tribe of Levi, must have been familiar with this fighting style because he’s believed to have killed the Greek General Nicanor with such a strike. Nicanor’s head and right arm would later be displayed at the Temple in Jerusalem and a festival marking the Maccabi’s victory would be observed for many centuries on the 13th of Adar.

Gad’s weakness would actually be that the tribe tended to see every situation exclusively from a military perspective. If they saw it as tactically necessary to retreat, they would retreat. And plan to confront the enemy again later.

But the tribe of Gad would often negate the non-military aspects of their actions. A retreat from battle can often have psychological or historical implications. And these concerns were for the most part not on Gad’s radar.

Israel then turned to Zilpa’s younger son Asher. The tribe of Asher, whose territory would be in the Galil, was known for producing high quality goods, delivered “to the royal table,” meaning for the benefit of the entire nation.

Bilha’s younger son Naftali would be given territory in the eastern Galil. His tribe’s priorities would be aesthetics and literature, which are essential values that provide cultural coherence to a civilization.

Having finished his brakhot to the sons of Bilha and Zilpa, Israel finally turned his attention to the sons of Raḥel. Yosef was in many ways well suited for national leadership. But despite his impressive material successes and high spiritual level, his aversion to what he considered to be narrow Hebrew particularism caused him to pursue improper means of accomplishing Israel’s universal mission. Yosef’s inner conflicts and his pull towards other peoples and cultures alienated him from his brothers and left him ineligible to lead the nation. He could successfully rule Egypt because Egyptian royal power was characterized by isolation from the general public. But leading the tribes of Israel would require personal interaction, love and acceptance from the people.

When Israel would eventually need a Yosef-type of figure to unite the tribes and establish a monarchy, that figure couldn’t have come from Ephraim or Menashe. Shaul ben Kish – our first melekh – would come from the tribe of Binyamin.

But three generations later, after the Davidic kingdom would split into the kingdom of Yehuda and the kingdom of Israel, the kingdom of Israel would most often be ruled by a tribesman of Ephraim. This for the most part made the Israeli kingdom more materially successful than its Judean counterpart. But it also made it more susceptible to foreign cultural and ideological influences that eroded its identity and caused many of its citizens to succumb to various forms of idolatry.

Israel ended Yosef’s brakha by stating in verse 26 that he was receiving from his father a greater brakha than Yaakov had received from Yitzhak and Avraham but also pointing out the challenge of Yosef’s estrangement from his brothers.

Finally turning to his youngest son Binyamin, Israel stated in verse 27 that “Binyamin is a predatory wolf; in the morning he will devour prey and in the evening he will distribute spoil.”

Binyamin was the only son of Yaakov born in the Land of Israel, making him an Israeli from birth. He was also the only member of the clan that hadn’t bowed to Esav because he hadn’t yet been born when that encounter had taken place. As a result, the Holy of Holies on the Temple Mount would be in Binyamin’s tribal territory. And, as already mentioned, Shaul ben Kish – the first official king of the unified Hebrew tribes – would descend from Binyamin.

In some regard, the status of the Hebrew tribes were determined by their relation to Binyamin because Binyamin possesses the power to unify Israel. Representing the future generation, the force of Binyamin can also strongly influence our national trajectory. When Yehuda and Yosef debated Binyamin’s fate at the beginning of Parshat Vayigash, their confrontation over with which of them their youngest brother would remain was on a deeper level actually a debate over which of them represented the true continuation of the patriarchs. But when the Hebrew kingdom later split following the death of Shlomo ben David, Binyamin chose to remain together with Yehuda, Shimon and Levi in the Judean kingdom while the other tribes formed the Kingdom of Israel under the leadership of Yosef’s Ephraim tribe.

As Israel’s brakha suggests, the tribe of Binyamin can be very dangerous to its enemies. Those who get in its way are at risk of being torn to shreds. Being the youngest of the family, Binyamin may have also been sensitive to being controlled by more dominant older brothers. The tribe inherited this defiant trait and this would eventually have tragic results where the tribe of Binyamin would let its unwillingness to be controlled by others lead it into war with all the other tribes – a war in which nearly all of Binyamin would be wiped out.

A brakha should be seen as a clarification. Israel was essentially revealing the inner essence of each son. And his brakhot to each one demonstrated that all twelve tribes together form one nation, and when we understand that we all comprise a single national entity, even with all of our individual shortcomings, we can successfully achieve a state of equilibrium and harmony.

The unity of the Hebrew tribes cannot be achieved through uniformity. Because each tribe is so different and unique, and there is so much variation in the brakhot we received, the nation of Israel expresses an example of Divine unity.

Israel ultimately demonstrates the unity and Divine Oneness of the Creator, not through like-minded conformity, but through the harmony of complementary differences.

After finishing the brakhot, Israel once again requested of his sons that they bury him in the cave of Makhpela alongside Avraham, Sarah, Yitzḥak, Rivka and Leah. The cave that Avraham had purchased as a family tomb because Sarah had been so insistent that Hebron be the family’s main base of operations.

B’reishit 50, verse 4 shows that after the mourning period for Yaakov had passed, Yosef requested of Pharaoh’s court to ask the monarch to grant Yosef permission to bury his father in Eretz Canaan. It’s noteworthy that after everything we had seen in previous parshiot about Yosef’s prominence and power in Egypt that he was no longer able to address Pharaoh directly to ask permission. As the memory of the great famine had by this point likely faded from Egyptian memory, Yosef’s contributions to the kingdom likely also faded from memory. The crisis had long been over and Yosef’s position in Pharaoh’s court appears to have been greatly diminished from what it had previously been.

Now that the systems and structures that Yosef created for the kingdom were able to function without his direct involvement, perhaps the elites began to regard him as an offensive foreigner and encouraged Pharaoh to distance him.

In verse 6, we see that Pharaoh granted Yosef permission to bury Yaakov in Hebron but specified that the permission had largely been granted because Yosef said he had made the oath to his father, showing that the oath itself had been warranted.

When the family returned to Hebron to bury Yaakov, our Sages teach us that Esav attempted to obstruct the burial, claiming the last remaining plot for himself. Despite their reunion in Parshat Vayishlaḥ, Esav was still set on reclaiming what he believed to have been rightfully his. This shows us a sharp difference between the potential relationships we can have with the people of Esav verses the people of Yishmael. In Parshat Ḥayei Sarah we saw that Yishmael recognized Yitzḥak and allowed him to take the lead when they buried their farther Avraham. By recognizing Yitzḥak, Yishmael creates the space for a potential partnership between us that could allow Israel to unite with the Islamic world and join forces in advancing Avraham’s vision.

But Esav refused to recognize Yaakov because ultimately Esav still wanted to be Israel, just as his spiritual heirs, the Roman Empire, Christianity and the modern West would claim to replace Israel or to usurp our universal mission in certain regards.

In any case, our Sages teach that when Yaakov’s grandson, Ḥushim ben Dan saw that Esav was preventing Yaakov’s burial, he quickly took action to decapitate Esav, whose head then rolled into the cave in reward for his having performed the mitzva of honoring his father.

We already learned that the power to defeat Esav exists within Yosef. And just as Shimon is the extreme expression of Yehuda and Amalek is the extreme expression of Esav, Dan is the extreme expression of Yosef. So it makes sense that a tribesmen of Dan would be the one to kill Esav.

After this, the sons of Yaakov worried that Yosef might still have been seeking revenge and had simply been waiting for their father’s passing. But Yosef emotionally reassured them that all was truly forgiven and they were finally able to reconcile in a way that all understood to be real rather than for the sake of pleasing their father.

And when it later came time for Yosef to leave the world, he told his brothers that the Creator would eventually take them out of Egypt and return them back to their land. He then made them swear that when the time came, they would carry his bones home with them.

This demonstrates that by the end of his life, Yosef had realized that his great political and economic successes in Egypt were not as central to the Hebrew mission as he had earlier thought. He realized that his vision of Israel influencing Egypt to be a light unto nations that would fix the world was not how the Hebrew mission must be fulfilled. He finally understood that the greatest contributions Israel can make to human development must happen through the influence of our own independent national framework in our own land.