Parshat Tetzave focuses on Aharon and his sons being consecrated as Israel’s kohanim.

How are Israel’s kohanim different from the spiritual leaders of other cultures?

How does the kehuna as an institution benefit the broader nation of Israel?

Why does the Torah place so much importance on the details of the priestly uniforms?

“The Hebrew Identity” podcast draws upon teachings from Manitou (Rav Yehuda Ashkenazi), Rav Kook, and many of Israel’s ancient sages to present the evolving story of the Hebrew tribes, as seen in the weekly Torah portion. The series focuses on what the unique challenges and personal growth of various Biblical personalities can teach us about our present day struggles.

For more content from VISION Magazine, subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on Twitter @VISION_Mag_, Facebook and YouTube. If you haven’t already, don’t forget to subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud, iTunes, Stitcher, TuneIn, or Spotify and leave a rating and review to help us get our message out to a wider audience!

To support the podcast, head over to our PayPal portal and be sure to write a note that your contribution is for the podcast.

Hosted by: Yehuda HaKohen

Transcript:

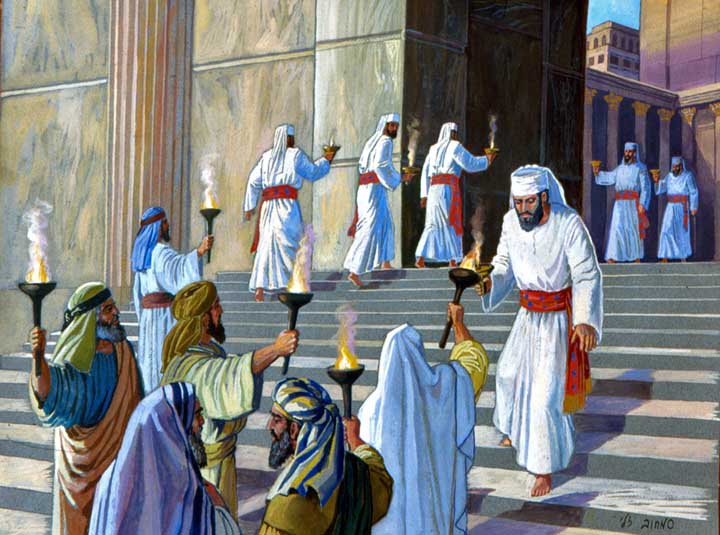

Parshat Tetzave spotlights the kohanim – the Hebrew priests from the tribe of Levi that directly descend from Aharon ben Amram.

What was common in ancient Egypt and many civilizations of that era was for a priestly class to live a privileged existence while working to appease national deities in such a way that would often empower the priests over the general population.

But one thing that distinguishes the kohanim of Israel from the priests of other peoples is that the kohanim serve on behalf of the people and its needs. Not to appease the Creator but to enable the conditions for Israel to benefit from a powerful spiritual experience and a meaningful encounter with HaShem.

This involves not only helping to cleanse the people from their transgressions through the korbanot but also inspiring the public’s imagination towards a connection with the Divine through creating the conditions to maximize the emotional impact of the Temple experience. Aesthetics therefore play a major role in the avoda. The sounds, smells and appearance of what takes place in the Mishkan and later the Mikdash were all designed to spiritually elevate and inspire the nation.

Transgressions are often fundamentally motivated less by logic and more by desires. As national public servants meant to liberate the people from their sins and bring them close to HaShem, the kohanim must present a vivid experience of kedusha that could compete with the temptations that would often lure Hebrews away from the path of Torah. Not intellectual rational arguments but an overwhelmingly emotional experience of holiness that could then strengthen each person’s desire to hear and accept the rational arguments of our ḥakhamim.

Just as the imaginative faculty is what often leads a person to sin, the kohanim would target that very same faculty in order to bring people close to Torah and to the Hebrew mission.

The role of the kohanim – and to a lesser extent also the entire tribe of Levi – is the powerful performance that opens people up to wanting to live lives of Torah in such a way that helps them participate in advancing Israel’s mission.

This was accomplished through the music of the Levites, the lights of the Menora, the performance of the sacrificial service, the taste of the meat, the smell of the incense – which according to some opinions might have included cannabis – and the uniforms of the kohanim themselves.

The b’gdei kehuna – the priestly uniforms – are specifically designed to stir the imagination and inspire a mental image of kedusha. Parshat Tetzave describes these uniforms in great detail. It actually first describes the four special additional garments worn by Aharon and every subsequent Kohen Gadol and then proceeds to describe the four garments worn by every kohen, because each priest should be understood as actually being a derivative of the High Priest.

Manitou teaches that the four garments worn by ordinary kohanim are meant to counter the four most serious transgressions inherent in human nature. These include the tunic, the sash, the turban and the pants.

The tunic represents restraining the body from violent behavior towards others.

The sash, which is 32 cubits long, wraps around the kohen’s waist and separates between the upper and lower body, specifically between the emotions of the heart and the urges of the male organ, in order to weaken the influence of sexual temptation on the heart – the lev – which has a numerical value of 32 in the Hebrew language.

The turban represents correcting the head from disrespectful attitudes and vulgar behavior towards others. The point of the turban is to slightly weigh down the head as a reminder of our accepting the Creator’s sovereignty. It’s also the precursor and inspiration for the kipa worn by many Jewish men until today.

The pants represent restraining and properly directing our sexual passions. They also have the function of modesty so that the kohanim shouldn’t expose ourselves to the floor of the Mishkan or Mikdash.

It’s important to note that the kohanim are prohibited from wearing any additional garments during the service. No jewelry. No bandages. No shoes. The kohanim must perform our work barefoot as a means of connecting physically with the floor and expressing our lack of independence.

The Kohen Gadol – who often comes into contact with the political and spiritual leaders of the nation – wears four additional garments to help counter more sophisticated transgressions.

One of these items – the ephod – serves to counter idolatrous inclinations. The ephod was like an apron – similar to what was worn by the priests of many ancient religions. Our Sages explain that while idolaters would wear a similar apron on the front of the upper body, the Torah prescribes that the Kohen Gadol wear it backwards and in a lower position.

This was meant to simultaneously disparage idolatrous practices and re-channel the cravings many idolaters had for spiritual connection. In the ancient world, humanity experienced a powerful spiritual reality that’s difficult for us to appreciate and many were pulled towards idolatrous rituals as a means of satisfying their cravings.

But with discipline and refinement, a Hebrew could access prophecy. And the ephod was designed to compel people to do the work of building themselves in HaShem’s service rather than settle for the quick spiritual fix provided by various forms of idol worship.

Next is the Kohen Gadol’s breastplate of judgement – the ḥoshen hamishpat. Each of the twelve precious stones in the breastplate reflects the unique characteristics of one of the twelve Hebrew tribes. This symbolizes the unity of the children of Israel.

But unity shouldn’t be confused with uniformity. The breastplate doesn’t feature one giant national stone or even twelve identical tribal stones, but rather twelve uniquely different stones – each expressing a different identity but fastened to the same collective breastplate worn by the High Priest – uniting the distinct tribes into a cohesive whole. Like the tribes of Israel, each stone is special and no two are identical – just as each tribe contributes its own unique values and identity to the larger nation.

Sh’mot 28, verse 30 states that “Into the ḥoshen hamishpat shall you place the Urim and the Tumim.” The Urim and Tumim are mentioned here, but their actual function isn’t explained. And the verses that will later describe the construction of the Mishkan and its vessels don’t mention them. So it’s possible that Israel had possessed them before this point and already understood their function.

The Kohen Gadol’s robe is designed to counter evil speech. At the bottom of the robe are little blue, purple and red pomegranates together with bells to remind us that the things we say about other people tend to spread and cause harm.

Finally, there’s the diadem worn on the Kohen Gadol’s head. It reads Kodesh LaShem and is designed to combat the sin of arrogance.

The Talmud teaches us in Yoma 35b that the uniforms of the kohanim must be made of materials that were contributed by the people and belong to the nation collectively. This demonstrates that the kohanim don’t constitute a privileged priestly class engaged in spiritual activities for our own benefit but are actually public servants tending to an important national need. We actually submerge our own personalities into the collective Hebrew nation.

It could even be said that the kohanim lose our individual identities when performing the service. In that sense we become similar to the Table, the Menora and the Alter. We to a certain extent forfeit our individuality and simply become a link between the children of Israel and HaShem.

Just like the other holy vessels, the kohanim must meet very exact specifications in terms of what we wear and how we live our lives. And in Parshat Tetzave, we see Aharon and his four sons, the first Hebrew kohanim, undergo a consecration process in order to be fit for use in the Mishkan and to effectively serve as intermediaries between Israel and HaShem just as Israel, as a “mamlekhet kohanim v’goy kadosh” – a “kingdom of priests and a holy nation,” is meant to serve as an intermediary between humanity and the Creator.