With the final election polls coming in, one can only predict what the final results and aftermath might be. To aid in these predictions will be available polling data, polling corrections from the previous elections, and current societal trends.

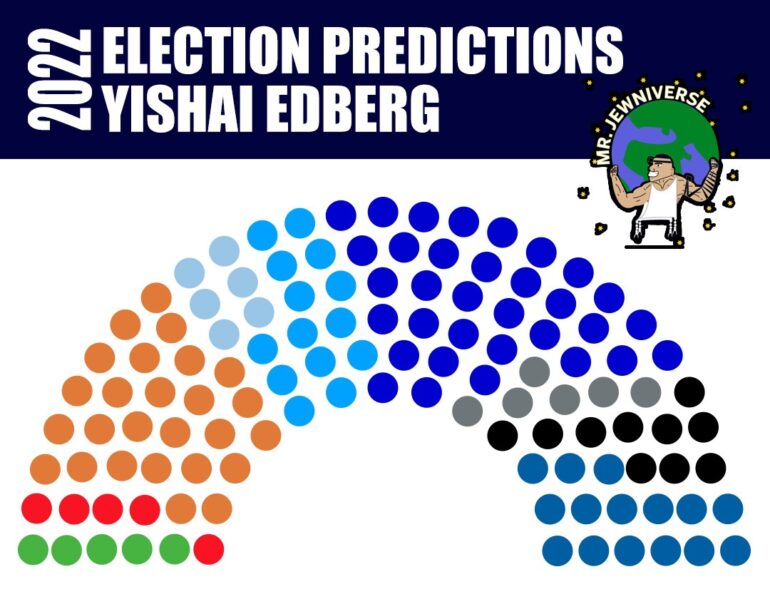

Likud (33) – Binyamin Netanyahu’s flagship is running an under-the-radar campaign currently polling at around 32 mandates. This strategy is very purposeful and yet unlike any other Netanyahu campaign. In previous elections, Bibi has thwarted attempts to outflank him, which in the past have been most often orchestrated by Naftali Bennett. This election, Netanyahu has instead decided to cede this ground to the Religious Zionism Party and focus on the economy and stable governance instead.

This retreat to the “center” allows Bibi to escape the “just not Bibi” attitude that was such a presence in the previous four election cycles, letting his own personality and the animosity directed at him be overshadowed by that of Itamar Ben-Gvir and the media’s hysteria over his recent upsurge in popularity. Bibi’s strategic retreat has turned him from the establishment’s villain into its unlikely possible savior from a Religious Zionism-included coalition. In short, Bibi has sacrificed publicity and votes to Religious Zionism, but in turn, has swapped “just not Bibi” with “save us Bibi.”

The Likud will likely split the difference between its March 2020 height of over 1.3 million votes and 36 mandates and its 2021 dip down to 30. Likud is typically polled very accurately and, perhaps with the help of Ofer-Bader reallocation, will win 33 seats.

Yesh Atid (26) – If Likud’s strategy is a retreat in the face of its potential coalition partners, the strategy led by Yair Lapid can be best described as an offensive. Yesh Atid has amassed considerable momentum, rising from an average of 18 seats in polls when the coalition collapsed to around 25.

This momentum, however, has come directly at the cost of its coalition partners. Labor and Meretz have each dropped a few seats in polls over the last six months and the momentum of Benny Gantz’s National Unity has stagnated and declined despite big mergers and additions.

Risking his potential bloc in the process, Lapid has firmly established himself as the face of Bibi’s opposition. While the previous election slightly overvalued Yesh Atid in polling, Lapid’s strong momentum should be able to carry him to 26 mandates.

Religious Zionism (15) – Betzalel Smotrich and Itamar Ben-Gvir have the two ingredients perfect for an election-day overperformance; momentum and a significant shy vote. Religious Zionism has been the success story of the past year, more than doubling its polling average at a steady yet increasing pace over the last 18 months.

Religious Zionism has benefitted the most from the collapse of Yamina from which they split before the previous election. They are also being aided by Netanyahu, who is going against his own election precedents to consciously cede ground to Smotrich and Ben-Gvir.

In the previous election, Religious Zionism was shown dancing with the electoral threshold up until the election itself, surprising the public by winning a healthy six seats. With more momentum, balanced by more animosity towards the party, there should be enough votes, proud and shy, to win the party 15 mandates.

National Unity (14) – Benny Gantz was the biggest surprise of the previous election. After breaking campaign promises to join a government with Netanyahu, splitting his union with Yair Lapid in the process, and then failing to maintain the stability of the coalition, most predicted the end of Gantz’s political career. But despite all polling placing Blue & White around the electoral threshold, Gantz about doubled expectations by winning eight seats.

Gantz is exactly the kind of politician Israelis will say they will not vote for and then vote for. He is inconspicuous, politically flexible, and boringly pragmatic. On Israel’s last election day, Gantz was not out on the streets or at the polls rallying votes, but in the halls and offices of the defense ministry. Israelis have a quiet respect for that kind of leadership, even if they don’t always say it.

On the other hand, politicians like Gideon S’ar, Yifat Shasha-Biton, Z’ev Elkin, Matan Kahana, and the like are exactly the kind of politicians Israelis will say they will vote for before coming home to Likud or going further for Religious Zionism. The banking on the mythical “middle Israel” (coastal traditional Ashkenazim) is a losing strategy. It was a losing strategy for New Hope, it was a losing strategy for Yamina, and it will not bare fruit for Gantz. This is especially true with the inclusion of Gadi Eisenkot, who has proven to be much more openly ideological and divisive than Gantz on issues of Jewish identity and territorial concessions.

According to a poll published in Davar after the last election cycle, Gantz and Lapid ran the parties with the most votes from Israel’s wealthiest sectors. Gantz’s attempts to reach beyond that base to the middle class may not yield any return, but the quiet goodwill and respect he has among many Israelis should still garner him 14 mandates.

Shas (10)- Shas has been running the best campaign of this election cycle. They have adopted the slogan “Jewish, nationalist, socially progressive” and are banking heavily on socio-economic issues. Aryeh Deri has made the welfare-cutting policies of Finance Minister Avigdor Lieberman his main target, promising instead an expansion of welfare programs for Israel’s poor.

There are four conditions that make this a strong campaign.

First, Israel’s current economic situation is conducive to an economically-focused campaign.

Second, Shas’s nature, grounded in its Council of Torah Sages, makes its stances on national and cultural issues abundantly clear, allowing Deri to focus on socio-economic issues without creating the impression of apathy towards the qualitative nature of Israeli society.

Third, the Likud’s liberal free-market approach leaves Shas an opening to win over Mizraḥi voters that would otherwise not vote for a “Ḥaredi party.”

Fourth, the many problems within UTJ could allow Shas to sway Ashkenazi Ḥaredi voters.

Shas has picked the right issues and the right slogans under the exact right conditions. For that, they should be rewarded with 10 mandates.

UTJ (6) – United Torah Judaism has a lot of problems and a lot of internal divisions. The clearest division is that between its Ḥasidic Agudat Yisrael and Lithuanian Degel HaTorah factions, which nearly split earlier this campaign over the former’s relative openness to greater math and science education. The former is also not so thrilled by the latter’s recent takeover of the joint slate. Moshe Gafni heading the list is the first time the joint faction has been led by a Degel HaTorah candidate.

The party is also divided over the legacy of Yaakov Litzman, the party’s leader from 2003 until 2021. Was Litzman a daring pioneer, the first Ashkenazi Ḥaredi to accept a ministerial post, unfairly prosecuted for his associations with Netanyahu, or was he a corrupt dreg who bungled the coronavirus pandemic and provided cover for sexual abusers?

Agudat Yisrael’s largest sect, Ḥassidei Gur, is undergoing an increasingly ugly split, causing many of its potential voters to skip election day. There is also a generational divide, with younger Ḥaredi Jews more supportive of the state and dissatisfied with the party’s narrow self-interest and relative lack of political participation on major national issues. Many are still upset at UTJ’s non-opposition to the coronavirus shutdowns and due to the effect the shutdowns had on Ḥaredi communities and lifestyles.

These divisions will cost UTJ many votes; many to Shas, many to Religious Zionism, and many just to apathy. But despite UTJ boasting a built-in base, it’s been polling steadily at seven and will likely still win a half-dozen seats.

Yisrael Beiteinu (6) – At one point, Avigdor Lieberman was thought to be the future of Likud politics. However, as his base of post-USSR immigrants acculturate and aged, his lot in Israeli politics continues to shrink.

By voter base, Yisrael Beiteinu is the oldest party. Its message of liberal free-market economics combined with Putin-esque strongmanerry is not popular with newer immigrants from the Former Soviet Union or the children of Lieberman’s once-strong base.

Yisrael Beiteinu peaked in 2009, winning 15 seats. Today it’s polling around six, which is what it will likely win.

Labor (5) – It is hard to believe that just a few years ago Labor was still the major party for Liberal Zionists. While Merav Michaeli’s leadership has so far saved the party from the extinction nearly wrought by the leaderships of Avi Gabbay and Amir Peretz, Labor has again begun to stagnate and decline.

Labor is in the middle of an identity crisis. It has firmly become a sectoral satellite party of Yesh Atid, no longer a bloc leader, leaving the party the choice to embrace this role and make the best out of it, becoming a narrow ideological party, or strive to regain its bloc-leading glory days, shunning ideological purity for a big-tent image.

Labor voters’ elevation of Michaeli along with the likes of Naami Lazimi and Gilad Kariv seem to show that they prefer the former, that Labor should focus on cultural issues like promoting westernized expressions of Jewish identity. However, Michaeli’s refusal to join with Meretz, to create a super-satellite ideological list in favor of maintaining Labor’s more moderate image shows that she herself might prefer the latter option.

Labor stands in the middle of the road. It’s a satellite party with the composition of a satellite party playing dress-up in a bloc leader outfit that no longer fits it. The party has enough support to secure five seats, but not much more than that.

Meretz (5) – In 2015, Zehava Galon promised to resign as party leader if the party won only four seats. In 2022, Zehava Galon returned to the Meretz leadership to save the party from falling under four seats.

Meretz was largely blamed for the collapse of the Bennett-Lapid government. It was Meretz’s Ghaida Rinawie Zoabi’s abandonment of the coalition which served as its final straw. Nitzan Horowitz, the party leader, resigned, as did former party leader Tamar Zandberg and party stalwart Issawi Frej.

Voters blamed Meretz too. While Meretz began the campaign just below the electoral threshold, the return of Zehava Galon to leadership should be enough of a momentum boost to secure the party five seats.

Ḥadash-Ta’al (0) – Palestinian voters seem to appreciate unity. The three times Ḥadash, Ta’al, Balad, and the United Arab List ran together as the Joint List, they won between 13 and 15 seats. When they split into Ḥadash-Ta’al and UAL-Balad in April 2021 they won just a combined 10 seats, and when UAL split for the previous election cycle, they won just 10 again.

So it was a big risk when Ayman Odeh handed in his party list with the omission of the Balad party. Immediately, polls showed Odeh’s slate dropping from a healthy six seats to just above the threshold.

Many are speculating that Odeh’s omission of Balad was to pave his way into a Lapid-led government, something Ḥadash and Ta’al have expressed openness to while Balad has roundly rejected. If this is true, Ḥadash-Ta’al would be following UAL’s example, a move they themselves attacked mercilessly over the past 18 months and a strategy that has not proven particularly popular in the Arab sector.

Ḥadash-Ta’al lost a lot of goodwill by abandoning Balad and positioning themselves to join a Lapid government. Combined with a projected historically low Palestinian turnout rate, it is unlikely that they will pass the threshold.

UAL (0) – The United Arab List took a big risk in joining the Bennett-Lapid coalition, a risk that has not entirely paid off. Their participation in the coalition was marked by internal strife and challenge from party supporters, lawmakers, and spiritual leaders. Throughout the past 18 months, they have polled consistently at four seats.

The recent riots in Shuafat, however, are likely the final nail in the coffin for UAL. The party’s justification to their voters for joining the government was a transaction; they would give Israel legitimacy through their participation and Israel would give their voters better material conditions, better living standards, better security, and better treatment. Critics of UAL arguing that the legitimacy they gave far outweighed any benefit they returned to their voters feel vindicated by Shuafat, pointing to it as an example of how little has changed despite UAL’s cooperation.

Dissatisfaction with UAL’s decision to join the coalition combined with overall low Palestinian turnout across the board will drown the party under the electoral threshold.

Balad (0) – Balad is the Knesset’s only Palestinian faction that seems to genuinely represent the feelings of their sector. Hadash is a communist party, Ta’al a puppet for Fatah, UAL the political arm of the Islamic Movement, but Balad seems to truly and solely represent the people. Unfortunately, the Palestinian citizenry is burnt out, disinterested, and will likely sit out in large numbers.

Balad has never won more than three seats and, splitting the Palestinian vote with Ḥadash-Ta’al, UAL, and apathy, they’re unlikely to do so in this election for the first time.

Jewish Home (0) – The kind of mainstream “Zionism-with-a-kipa” that Jewish Home represents belongs more in a museum than on a ballot today. Ayelet Shaked’s Likud-lite flavoring does not help much and carries with her the baggage of her broken promises and coalition dealings from the last two years. Jewish Home won’t be able to touch the electoral threshold in what may be their last election as a serious party.

Burning Youth (0) – Burning Youth is a party engulfed in flaming controversy. At one point, it was feasible to predict that TikTok personality Hadar Mukhtar’s party would amass enough momentum to push Burning Youth over the threshold or into an alliance with a stronger party.

But after months of bad press, public fatigue, and a scandal that has exposed either Mukhtar as a liar or her parents as tax-frauds, Burning Youth will burn out far before they reach the electoral threshold.

Aftermath – On election night, Netanyahu will declare victory and place his first call to Benny Gantz. It has always been his modus operandi is to govern from the middle, positioning himself as a sensible moderate to the media and the world and a chained fighter to his electoral base.

The decision to whether a 63-seat government is formed between Likud, National Unity, Shas, and UTJ will be made by Benny Gantz alone. Gantz will have to weigh the benefits of continued institutional power and preventing Smotrich and Ben-Gvir from becoming government ministers must be weighed against the goodwill he would receive from the many anti-Netanyahu hardliners for standing against Bibi.

If Gantz decides to stand firmly against Netanyahu, marching indignantly into the opposition, Netanyahu could form a 64-seat government with Religious Zionism, Shas, and UTJ.