Central to the Ḥanukah story, yet often ignored or dismissed in many of our cultural reproductions of the narrative, is the very real, very violent conflict between the Maccabean rebels and their Hellenized Jewish neighbors. While our central enemy was the Yevanim (Seleucid-Greek Empire), the first phase of the revolt was launched against the Judean adherents of Hellenic culture and civilization, the urban upper class who hoped to develop Jerusalem into a cosmopolitan center of the expansive Seleucid-Greek Empire.

Our modern sensibilities make the thought of disgruntled Jews waging violent war against their brothers to fight against Greco-Roman ideals truly frightening. But if we’re interested in understanding and identifying with the actions of the Maccabi fighters, we should try examining the geopolitical dynamics of the era using a modern theoretical framework.

The Macedonian (and later Seleucid) domination of Judea had a fundamentally colonial character. While this might at first glance seem like an anachronistic characterization, the key elements of economic extraction, political domination, and cultural conversion that characterize modern colonial pursuits were all present in the era of our Ḥanukah story, despite the absence of industrial capitalism, Westphalian nation-states, and Christian or European Enlightenment ideologies.

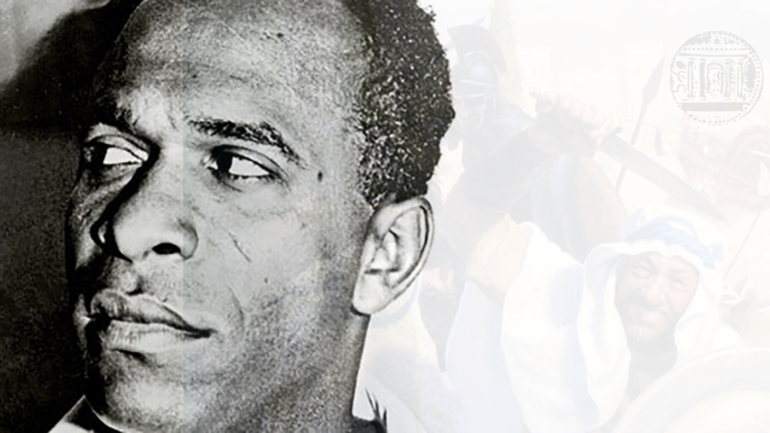

It may also prove useful to apply the theories of Frantz Fanon, preeminent postcolonial theorist, to the Maccabean Revolt. In his seminal work, The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon breaks down the relationships between three classes in the colonial ecosystem.

First, the “colonists” or colonizer class, which have come from the imperial center to enact the will of the colonizing power on the colonized land and people.

Next, the “native” or colonized class, who existed outside the colonial context simply as “us” before the act of colonization but who now, by necessity, are defined by their opposite, the colonists.

And finally, from among the native class there exists a “colonized intellectual” (or following liberation a “national bourgeoisie”) class who, despite their natural belonging among the natives, identify intellectually and culturally with the colonizers. They have accepted colonial ideology, colonial methods of production and economic systems, and colonial political paradigms as universal truths, seeing indigenous practices as backward, uncivilized, and even barbaric.

The tension and conflict between these three classes is essential to understanding colonialism, and its dissolution in the face of an anti-colonial struggle.

In our case, the characters of the Ḥanukah story can be clearly categorized according to Frantz Fanon’s paradigm. The colonists are the Seleucid imperial administration, military, and the Syrian-Greek peoples that settled in Judea for economic opportunity, especially along the coastal areas and in the larger cities.

The Judean masses, along with more rural members of the priestly families – foremost among them the Hasmonean family of Matityahu ben Yoḥanan – can be classified as the natives, living their traditional agricultural lives, until their conquest and domination by the imperial armies of Alexander the Great, and his Seleucid successors.

Finally, the Hellenized Jews, largely members of the wealthier and more urban segments of Judean society, represent the colonized intellectuals who have “adopted the abstract, universal values of the colonizer.”

It is against this adoption of the values of the colonizer, both through compulsion and through cultural and material exchange, that the revolt broke out. As Frantz Fanon writes, the natural response of the colonized to Western culture, especially after a period of domination and repression of indigenous culture, is pulling a knife. While the Seleucid colonists, and their Hellenized Judean interlocutors celebrated Greek ideals of beauty, truth, and the individual, the Hasmonean rebels focused on the values that had been truly important in Judean society.

While Fanon, in his characterization of modern national liberation struggles, highlights “first and foremost the land” as the primary value, we have traditionally focused on three pillars – the nation, the land, and the Torah – as the pillars of our society, and the Maccabees were no exception.

This is not to say that the land wasn’t gravely important to our heroes. As Matityahu’s last surviving son Shimon declared, “We have neither taken foreign land nor seized foreign property. We have returned to the inheritance of our forefathers, from which we had been unjustly banished by our enemies… Now that we have the opportunity, we are firmly holding onto the inheritance of our fathers.”

This should be understood, not only as an assertion of the Judean claim to the land of Judea, but also as a fundamental rejection of the Greco-Roman universalism that sought to justify imperial domination in the name of civilization and progress. It should be understood as favoring a worldview that recognizes the unique contributions and role of each culture and acknowledging that each nation is an essential part of the collective whole of HaShem’s creation.

Therein lies the crux of the military and cultural revolt led by Matitayahu and his sons against “native” Hellenism and foreign Seleucid domination. For those who were not wooed by the hollow material lure of Greek gymnasia, bathhouses, theaters, and temples, “all the mediterranean values… [turned] into pale, lifeless trinkets… Those values which seemed to ennoble the soul [proved] worthless because they [had] nothing in common with the real life struggle” of the average Judean under Seleucid occupation. Resisting the spread of these destructive ideologies was not just a national interest, but a moral imperative in the Torah-based value system of the Judean masses.

Most importantly, in the Maccabean revolt, as in all liberation struggles according to Frantz Fanon, individualism is the first of all the Western values to be laid bare by the light of the struggle. However, beyond the natural camaraderie of the trenches that emerges in modern struggles against colonial domination, the intrinsically entwined pillars of nation, land, and Torah reinforced the communal, even familial, nature of the Hasmonean revolt.

Even prior to the outbreak of violence, by maintaining their connection to the Torah and to Klal Yisrael – the collective national spirit – the Judeans had a natural antidote to the draw of Hellenic individualism.

Fanon’s understanding, though not perfect when extrapolated to the Ḥanukah story, provides a broad framework for better understanding the motivations and the strengths of the Maccabi guerrillas. Their apparently harsh reaction to Hellenic values, not just from the Seleucid colonists but even (and especially) from Hellenized Judeans, is a natural reaction by natives to a foreign culture that has undermined their traditional way of life.

Individualism is especially suspect, and its rejection, in keeping with the traditional Judean emphasis on nation, land, and Torah provided a basis for the collective national effort toward liberation, which succeeded in large part due to its broad appeal to those Judeans who felt a connection to the collective ways of their ancestors.

And finally, the broad rejection of the universal value system that “justified” the Seleucid domination created its own justification for the revolt, and the reassertion of Judean autonomy in “the inheritance of our forefathers.”