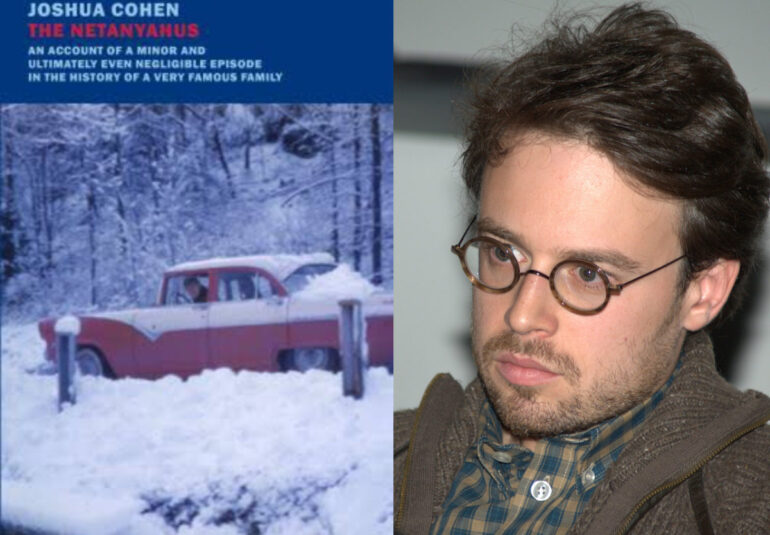

Joshua Cohen’s newest novel, The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family, is a well written and humorous look at Jewish identity and the American Jewish experience.

The novel was inspired by an anecdote shared by literary critic Harold Bloom about the time that he hosted Benzion Netanyahu and his family at Cornell University, including 13-year-old Yonatan and 10-year-old Benjamin. Through the famous Israeli family’s visit, and the events leading up to it, Cohen asks American Jews to consider whether assimilation is worth the cost of our national identity.

***Warning: Spoilers Ahead***

The Netanyahus works as a clever allegory on American Jewish life. Set in the late 1950s, it paints a picture of how the American Jewish experience sixty years ago set the stage for the conditions of American Jewry today. The novel is narrated by Ruben Blum, an American history professor at the fictional Corbin University. Cohen portrays Blum as a somewhat sad character who takes great pride in being the first (and only) Jew on the university’s faculty. He works hard to fit in and doesn’t complain when his colleagues force him to play Santa Claus at their annual Christmas party. Nor does he resist when the Department Chair informs Blum that he is to host Benzion Netanyahu on his upcoming interview for a professorship position since they are both Jews.

Most of The Netanyahus is about Blum and his family. Cohen compares Blum’s Yiddish-speaking parents that see America as the best option for now until the gentiles turn on the Jews, with Blum’s wealthier in-laws, who pretend to speak French, and do their outmost to embrace bourgeois culture, despite not really understanding it. We meet Blum’s bored wife and unhappy daughter, who goes to dramatic lengths to “fix” her nose.

But the book is most powerful in how it contrasts Blum’s confused and uninspiring family with the Netanyahus.

The elder Netanyahu is not afraid to challenge Blum’s colleagues and the Netanyahus seem not to care how they are perceived by Americans or the Blum family. Even though Cohen tries to shock us with crude manners and bad behavior, including a controversial sexual episode, the Netanyahus come off as confident, proud, and alive.

Cohen introduces us to Benzion Netanyahu’s Revisionist Zionist background and his academic work centered on medieval Spain and the Jews. Netanyahu’s thesis seeks to debunk the widespread belief that the Inquisition arouse in response to Jews that converted to Christianity while secretly practicing Jewish rituals. Netanyahu posits that most of the Jews of Spain that chose to remain after the Spanish Expulsion enthusiastically embraced Christianity and Spanish culture. He argues that the Inquisition was a political tool aimed at stopping Jews from assimilating into Spanish society. It’s hard not to see the parallel that Cohen draws to American Jews.

But the most poignant part of the novel is Netanyahu’s lecture at Corbin University. It is here that Cohen’s allegory turns into a direct challenge to American Jews, asking us whether we really want to trade in our Jewish identity for an empty, temporal American life:

“Your chances for survival-none at all. You, Ruben Blum, are out of history; you’re over and finished; in only a generation or two the memory of who your people were will be dead, and America won’t give your unrecognizable descendants anything real with which to replace the sense of peoplehood it took from them; the boredom of your wife . . . the craziness of your daughter isn’t just the craziness of an adolescent . . . it’s more like a sense of having not lived fully in a consequential time . . . like a raging resentment that nothing she can find to do in her life holds any meaning for her and every challenge that’s been thrust at her- from what college to choose to what career to have- is small, compared to the challenges that [Israeli children] . . . will one day have to deal with, such as how to make a new people in a new land forge a living history. Your life here is rich in possessions but poor in spirit, petty and forgettable, with your frigidaires and color TVs, in front of which you can munch your instant supper, laugh at a joke, and choke, realizing that you have traded your birthright away for a bowl of plastic lentils…”

It’s refreshing that an American Jewish writer is still willing to ask questions that many mistakenly think have long been settled. Not surprisingly Cohen has been compared to Philip Roth and other great American Jewish writers. The Netanyahus is well worth your time.