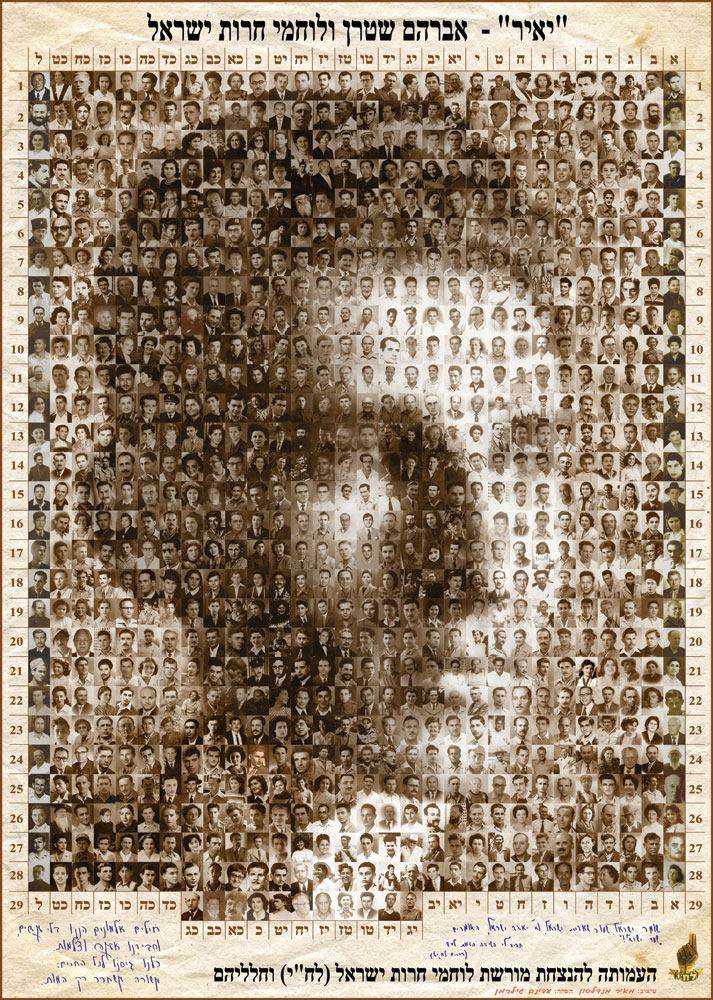

The first of Shvat marks the day Dr. Israel Eldad left our world. Eldad served as the ideological leader of the Leḥi (Fighters for the Freedom of Israel) underground that led the anti-colonial struggle against British rule in Palestine. He assumed this role once the movement recovered from Avraham “Yair” Stern’s assassination in 1942 and maintained it until the British fled the country in 1948.

Following the establishment of the State of Israel, Eldad spent the rest of his life agitating for the advancement of Jewish liberation beyond what Zionist thinkers were psychologically ready to imagine. Unlike the Zionist leaders, who regarded the Jewish state as the achievement of their project, Eldad saw the state as a tool with which to achieve the children of Israel’s ancient longings.

Early Life

Eldad was born Israel Scheib in Pidvolochysk, Galicia to a traditional Jewish family in 1910. During the first World War, the Scheibs wandered as refugees until ending up in Lvov. Israel’s father Leib had played a major role in developing his son’s worldview, infusing him with a love of Jewish history, tradition and general intellectual pursuits. His mother Fruma came from a Ḥasidic family and had married Leib at age seventeen over the objections of her parents.

Eldad would later say of his mother that “from her I inherited creativity and a love of life.”

Leib was self-educated Zionist and a highly skilled craftsman, having made all the family’s furniture and the children’s toys by hand. Until 1914, he had worked as a miller to support his family but once the Great War broke out, he fled with his family to avoid being drafted into the Austro-Hungarian army.

The family of five spent the war as refugees, suffering poverty and oppression in Ternopil until finally settling in Lvov and opening a bakery in 1918. That year, eight-year-old Israel Scheib witnessed a local funeral procession for several Jews murdered by the Polish army in a pogrom – an event that would have a profound impact on his understanding of Jewish vulnerability and power relations.

Leib recognized great intellectual potential in his son and encouraged him to develop his writing skills. After four years in a Polish school, the 16-year-old Israel was sent to the Jewish gymnasium in Lodz while also attending night classes and learning Hebrew and Jewish studies with a tutor.

In the gymnasium, Israel began studying Nietzsche and developing his own Jewish nationalist outlook. He also began to assert his independence in various ways and display what many would call an obstinate personality. In 1928, he heard Z’ev Jabotinsky speak in Lodz and felt himself agreeing with much of what the Zionist leader had to say – especially in regards to the establishment of a Jewish state.

Jabotinsky’s Revisionist Zionist movement occupied the right wing of the Zionist political spectrum, emphasizing the urgent need for a nation-state alongside a European-style Jewish nationalism that appealed to young Jews who had experienced anti-Semitic violence and intimidation from gentile neighbors.

Israel decided against joining Jabotinsky’s movement and instead moved back to his family’s home in Lvov the next year to decide his future.

Ignoring his attraction to the theater, Israel enrolled at both the Rabbinical Seminary of Vienna and the University of Vienna, where he completed his doctorate on “The Voluntarism of Eduard von Hartmann, Based on Schopenhauer.” He never took his “rabbinical exams” at the seminary and would later express criticism in his memoirs written after the underground period against the phenomenon of “Dr. Rabbis” and the westernization of Jewish values.

Following the 1929 outbreak of British-incited Arab violence against Jews in Palestine, Scheib attended a demonstration with his father in front of the local British Consulate. The following year, he discovered a piece by the revolutionary poet/prophet Uri Zvi Greenberg, “I’ll Tell It to a Child,” about a messiah who cannot redeem his people because they are not ready to accept redemption.

Eldad would later say that the poem caused a tremor in his heart and greatly influenced the development of his worldview. In 1932, he met and befriended Uri Zvi at a speech the poet was giving entitled “The Land of Israel is in Flames.”

That same year, Israel met the daughter of a Ḥasidic merchant named Batya Waschitz. Their courtship lasted five years and they married in 1937.

Between the Revisionists & Sternists

Scheib’s first job after graduation was teaching high school in Volkovisk. He also joined the staff of the Teachers Seminary in Vilna in 1937, while this city was part of Poland, and became active a local branch of Jabotinsky’s Revisionist Zionist Betar youth movement. Betar emphasized honor and a militant nationalism that appealed to young Jews in eastern Europe seeking empowerment in a hostile world.

Although he saw value in Betar, Scheib experienced frustration with the ideological limitations of the Revisionist movement. At the 1938 Betar conference in Warsaw, Scheib and Menaḥem Begin challenged Jabotinsky’s refusal to raise arms against the British Empire that then ruled Palestine.

This challenge to Jabotinsky led to Scheib being introduced by Natan Friedman-Yellin to Avraham “Yair” Stern, a member of the Etzel (National Military Organization) high command in Palestine who had been organizing secret cells within Betar that would receive military training for an eventual armed struggle against the British regime.

When World War II broke out, many Revisionists felt an obligation to remain in Europe and organize anti-German resistance activities to defend Jewish communities. The Sternists comprising the Etzel cells, however, viewed the central fight as the struggle to free Palestine and establish a free Hebrew state. The Scheibs managed to use forged exit visas to get past Soviet authorities and travel to Istanbul, where they learned that the Sternists in Palestine had split away from the Etzel to organize a new revolutionary underground under Yair’s leadership.

Most of the Betar leaders traveling with Scheib, including Friedman-Yellin, would join the Sternists once in Eretz Yisrael.

Leḥi

In April of 1941, the Scheibs arrived in Haifa. It didn’t take long for Israel to meet with Yair and join the movement, originally being kept separate from the underground framework but assisting Yair in formulating the group’s ideology.

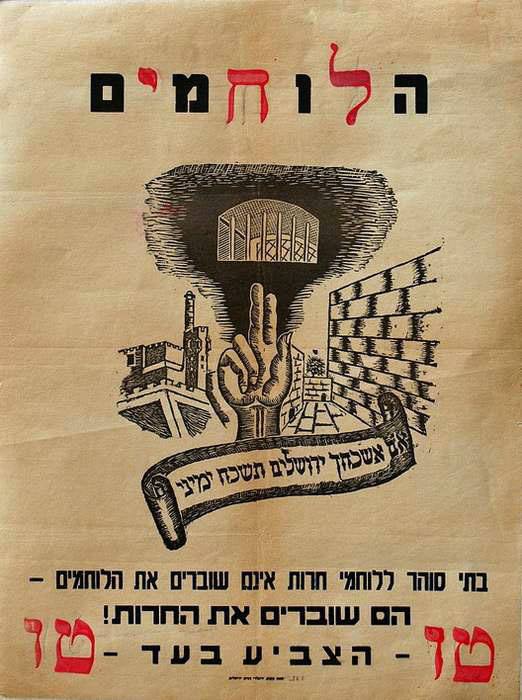

The two edited the newspaper BaMaḥteret, which demanded that the fight to free Palestine from British rule take priority over working towards Nazi Germany’s defeat. Assisting the British war effort was portrayed as a betrayal of the Jewish liberation struggle because the Jewish people first required independence in order to participate in the war as a player with its own interests. Because British colonial rule was the primary barrier to that independence, resources should be primarily directed towards the anti-British struggle.

The Sternists further argued that to enlist in the British military without a Jewish war aim (active rescue of Europe’s Jews, destruction of Nazi transportation lines, opening Palestine’s borders to Jewish refugees, guarantees of statehood, etc.) would be an act of betrayal of Jewish values akin to idolatry.

Following Yair’s assassination in February 1942, Scheib continued to write in the Sternist newspaper under the nom de guerre Sambatyon, arguing against Jewish enlistment in the British military: “We are opening a second front against Britain, that of the Hebrew nation, the front which will determine our fate not just in the present, but for all generations, the front of liberation!”

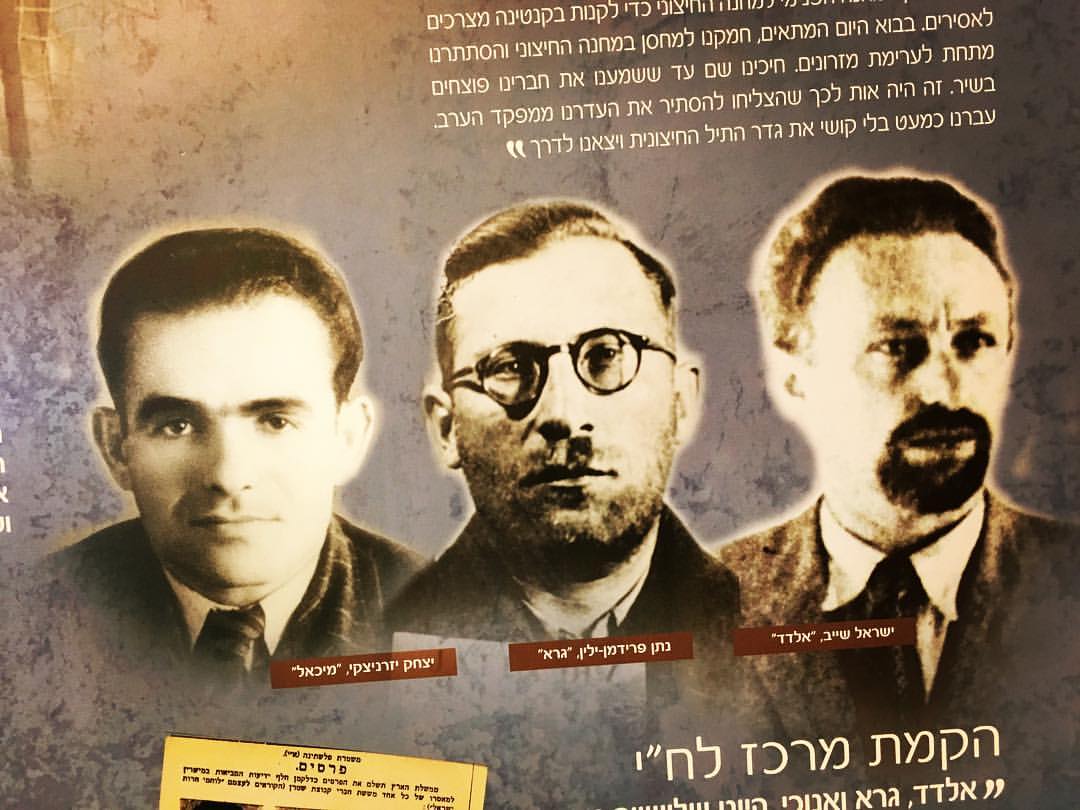

Because Yair had kept Scheib isolated from the underground, he escaped the brutal assassinations and arrests that almost decimated the movement. As the Sternists initiated a series of daring prison breaks and began reorganizing the underground into Leḥi in 1943, Scheib joined the three man center together with Friedman-Yellin, now known as “Gera,” as well as “Michael” – who would later become best known as Israeli Prime Minister Yitzḥak Shamir.

Gera was the group’s political leader and Michael was responsible for operations. Scheib, now going by the underground name “Eldad,” began to formulate the movement’s ideology. He also wrote many of the speeches for Leḥi fighters to deliver in court, where they would refuse to recognize the legitimacy of British rule or right to judge.

It was around this time that Gera wrote to Eldad, clarifying that “We must stress with great emphasis that we are not a Zionist movement. Zionism is empty of all content and no longer compels us forward to accomplish anything more. We are not a Zionist option and it is not our duty to bring this or that party back to the proper path. We are the Hebrew liberation movement in the land of Israel. For us, Zionism is dead and we no longer wish to busy ourselves trying to revive it or anything else of its kind.”

In his column Avnei Yesod (Foundation Stones), which appeared in the Leḥi journal HeḤazit, Eldad argued that:

The Hebrew freedom movement does not aspire to sovereignty because by its own will it is already sovereign. Just as the Greek is in Greece and the Indian is in India – in spite of the temporary occupation by foreigners. We aspire to and struggle for sovereignty – be there anti-Semitism or not, problems or not, refugees or not.

We do not hesitate to affirm that our existence is a sufficient expression of the sovereign aspiration of the vital freedom movement, which is not planning for another exodus from Egypt but a David-like conquest. Just as France will not be judged by the millions who capitulated but rather by the few who fought, so will Israel’s rejuvenation be judged by us, the vanguard of Hebrew liberation.

[The Land of Israel] is ours even without the Jewish Legion, without the NILI, without the Balfour Declaration or the Mandate. The Fighters for the Freedom of Israel are, first and foremost, liberators of the land of the Jews from foreign rulers. We do not recognize the Mandate, nor do we seek better patrons. The meticulous fulfillment of the British Mandate is of no interest to us…

The Zionist movement has until now, recognized the rights of England. Those who limit their struggle to the confines of ‘The White Paper,’ admit, in so doing, to England’s right of mastery here. A struggle against a specific law is a tacit admission of the right, in principle, of the lawgiver to legislate. It implies a desire for a better law. We deny England this right of legislation for we regard it as an occupying power against which actual war must be waged.

In 1944, Eldad was arrested by British forces. While fleeing from a Tel Aviv apartment, he fell from a water pipe and suffered injuries that required him to wear a full body cast while imprisoned in the Jerusalem Central Prison. He continued his political and philosophical writings from his cell and maintained communication with Gera and Michael through smuggled notes. After being transferred to the Latrun detention camp, he was rescued by Leḥi comrades while on a visit to a dentist’s office in 1946.

After two Sternist agents, Eliyahu Ḥakim and Eliyahu Bet-Zuri, succeeded in killing Lord Moyne – the highest ranking British official in the region, the official Zionist leadership and its Hagana militia initiated the Saison – hunting down Etzel and Leḥi fighters on behalf of the British authorities. But once Gera issued a clear threat to Hagana commander Eliyahu Golomb, the Saison limited its activities to only target the Etzel.

In September 1945, the Saison ended and a united Hebrew Resistance Movement was formed, comprising the Hagana, Etzel and Leḥi. But this effort only lasted nine months as the Zionist politicians directing the Hagana had no real interest in fighting British imperialism. Even the Etzel spoke of the British rulers as the “oppressive regime” and fought for the sake of improving British policies. Only Leḥi referred to the British as the “foreign regime.”

Leḥi had developed a sophisticated political outlook that applied principles of revolutionary theory to the Jewish people and its struggle for liberation, often also employing deep themes from Jewish history and ancient texts.

The underground identified and targeted major British economic interests in Palestine in order to make the price of occupation more expensive than the benefits of exploitation. One such example was the Haifa oil refinery, which Leḥi blew up on March 31, 1947.

As the struggle for freedom was intensifying in 1947, the British announced on September 27 that they would withdraw from the country and handed responsibility for Palestine over to the newly formed United Nations.

Following the November 29, 1947 publication of UN General Assembly Resolution 181, calling for the partition of Palestine into two separate states, Gera and Eldad published a declaration opposing the resolution: “The Freedom Fighters of Israel will continue to fight for the unity of the land with the proper tactics for each time and place.”

Eldad likened the Jewish reaction to the UN partition plan to the Biblical Hebrews dancing around the Golden Calf.

In late 1947, a new Leḥi daily, HaMivrak, began to appear. Under the headline, “Our Vision for a Just State,” Gera called for a socialist society, expanding on views he had previously expressed in HaMaas. In this essay, he called for equal opportunity for every child, universal education, and a state of justice and equality.

Approaching Israel’s Declaration of Independence, the Leḥi center decided to demobilize its fighters so they could enlist in the new Israeli army. In Jerusalem, however, Leḥi remained an independent force that continued to fight for the city’s liberation and inclusion in the Jewish state.

On September 17, 1948, the Sternists successfully carried out the assassination of Count Folke Bernadotte, a Swedish diplomat and UN representative attempting to internationalize Jerusalem. Eldad called the operation Leḥi‘s greatest gift to the Jewish people.

Following the assassination, many were arrested by Israel’s provisional government and brought before a military tribunal. Eldad managed to escape capture until a general amnesty was declared.

Advancing Israel Further

Most of the Sternists, under Gera’s leadership, formed the Fighters party. in order to compete in the elections to Israel’s first Knesset. The party identified its ideology as revolutionary socialist and included both Jewish and Arab veterans from Leḥi on its list of candidates.

The Fighters party exhibited a political sophistication and ideological creativity unique to Sternists that transcended Israel’s shallow left-right binary. Among its positions were:

- The entire Land of Israel under Jewish sovereignty

- Equality for Arabs and other non-Jewish populations

- A planned economy

- Opposition to the colonialist policies of the British Mandate legislation – most notably the defense emergency regulations – being incorporated into the State of Israel’s legal system

- Regional neutrality in the Cold War

- A united front with the other Semitic peoples to protect the Middle East from the designs of imperialist powers

The party only received 5,363 votes and Gera became its sole representative in Israel’s parliament. Two years later, the first Knesset was dissolved and the party fell apart.

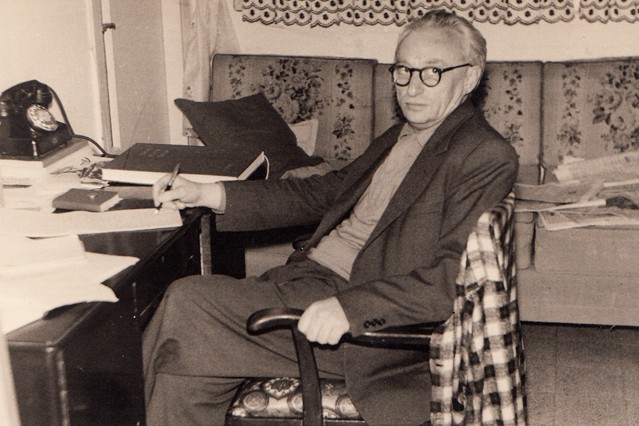

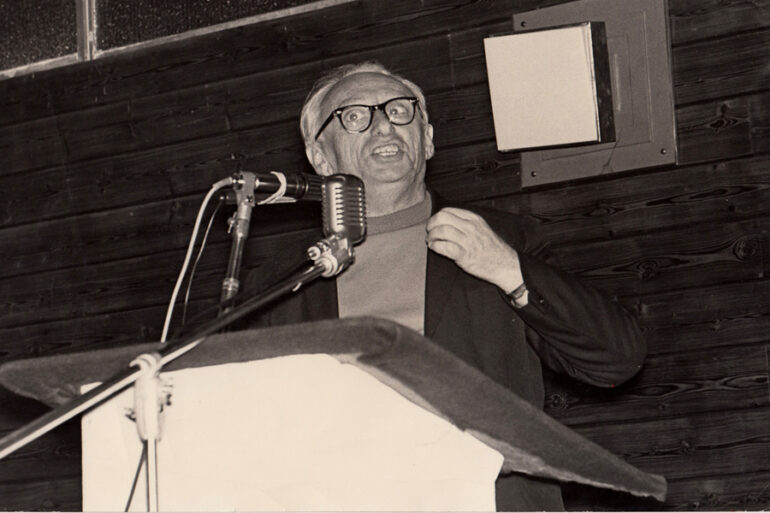

At one Fighter’s party meeting, Eldad had lectured on the Sulam (ladder) that Yaakov had dreamed of connecting heaven and earth, relating to the newborn State of Israel as the ladder between the Jewish people’s exile and redemption. For the next 14 years, he would publish a revolutionary journal, Sulam, together with former Leḥi comrades.

Although Eldad had been a candidate on the Fighters list, he had been skeptical of electoralism and had already begun to devote his energies to Sulam, which he used to promote the idea that a State of Israel was never the goal of the Jewish people’s historic revolution, but rather a tool with which to achieve our deeper historic aspirations.

For nearly two decades, the state existed in truncated borders as a result of the 1948 War’s armistice lines. During these years, Eldad agitated for Israel to conquer Jerusalem and other portions of the land under Jordanian and Egyptian control.

Eldad began teaching Tanakh and Hebrew literature at a high school until Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion intervened to have him fired. The prime minister was afraid Eldad would imbue the students with Leḥi ideology and therefore claimed it was dangerous to allow him to teach. Eldad took legal action and won in court but few were willing to hire him after Ben-Gurion had labeled him a danger to the state.

Eldad turned to literary work, wrote of underground battles, a newspaper-style review of Jewish history called Chronicles, a book of Torah commentary, Hegionot Mikra, weekly newspaper columns and encyclopedia entries. He also translated the complete writings of Friedrich Nietzche from German into Hebrew.

In 1962, Eldad became a professor of humanities at the Technion in Haifa, where he would teach for twenty years. In 1982, he began lecturing at what would become the Ariel University Center of Samaria. He also lectured, perhaps ironically, at Ben-Gurion University in the Negev.

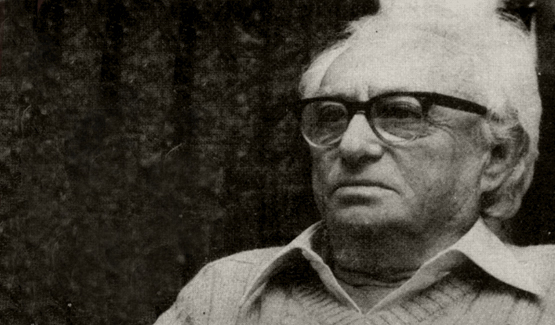

After the 1967 Six Day War, Eldad helped found the Land of Israel Movement that opposed any surrender of the territories won during that war. He also encouraged efforts to create Jewish communities in the territories, allying himself with Gush Emunim and involving himself with various nationalist political parties.

In 1988, Eldad was awarded Tel Aviv‘s Bialik Prize for his contributions to Jewish thought.

He continued throughout his life to fight for the land of Israel, opposing any attempt to divide her. Although this sometimes brought him into conflict with former friends and comrades, he never veered from his loyalty to the Jewish people’s vision of redemption.

On the first of Shvat, 5756 (January 22, 1996), Eldad left the world. His funeral was attended by notable public figures including Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu, former Sternist operations leader Prime Minister Shamir, and Knesset Speaker Dov Shilansky.

Dr. Israel Eldad was buried on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, at the foot of the grave of his mentor and friend, Uri Zvi Greenberg.

I would like to edit and rewrite this:

When World War II broke out, many Revisionists felt an obligation to remain in Europe and organize anti-German resistance activities to defend Jewish communities. The Sternists comprising the Etzel cells, however, viewed the central fight as the struggle to free Palestine and establish a free Hebrew state. The Scheibs managed to use forged exit visas to get past Soviet authorities and travel to Istanbul

so:

When World War II broke out, unlike other Zionists who decided to remain in Poland or even return once they reached the Soviet zone of occupied Poland to support the fellow movement members, many Revisionists sought to reach Palestine as they considered themselves already enlisted in the Irgun cells, to fight and free Palestine to establish a free Hebrew state. The Scheibs, together with the Begins and the Friedman-Yellins and several hundred others reach Vilna by Ocotber 1939. In June 1940, the Soviet Union took over Lithuania. It required forging exit visas to get past Soviet authorities and travel to Istanbul. Begin and others arrested by the Soviets were left behind.