The tenth of Tammuz marks the anniversary of Prime Minister Yitzḥak Shamir’s passing. Despite his many contributions to the Jewish people as the operational leader of Leḥi (Fighters for the Freedom of Israel), a top agent of Mossad and Israel’s strongest prime minister, Shamir has essentially been written out of history.

Shamir’s Early Life

Shamir was born Yitzḥak Ysernitzki in Rujenoy to a traditional Jewish family in 1915. His father Shlomo, a leather worker and head of the local Jewish community, provided his son with a Hebrew day school education. Violent expressions of anti-Semitism were regular occurrences in the small border town of Rujenoy, which often changed hands between Russia and Poland.

In 1929, the young man joined Z’ev Jabotinsky’s Revisionist Zionist Betar youth movement. Occupying the right wing of the Zionist political spectrum, Betar emphasized honor and a militant nationalism that appealed to young Jews in eastern Europe who had experienced anti-Semitic violence and intimidation from gentile neighbors.

Yitzḥak enrolled at the University of Warsaw and began studying law, but this didn’t last long. His attention was far more focused on the ingathering of his people back to the land they had been displaced from.

What became my raison d’être, what moved me and was to rivet my attention, undiminished, for the rest of my life, was the return of the Jews to the Land of Israel – a drive so intense, an idea so powerful, that all other options before me in Warsaw could in no way compete.

Aliya

Yitzḥak Shamir dropped out of law school and moved home to Palestine in 1935. At first, he found work as a construction worker and later an accountant. He enrolled in Jerusalem’s Hebrew University but when Palestine’s British rulers incited Arab violence against the local Jewish population, Yitzḥak joined the Etzel (National Military Organization) and became both an intelligence agent and a fighter in a unit responsible for reprisal attacks on Arab targets.

It was around this time that the Ysernitzki family in Rujenoy, Yitzḥak’s parents and two sisters, were rounded up by the invading Germans and ultimately killed in the Shoah.

When a number of Etzel commanders, led by Avraham Stern (better known as “Yair”), came to the conclusion that the fight for Jewish liberation must be directed against British imperialism, Yitzḥak Shamir joined them in breaking away from the Etzel and establishing a revolutionary underground that ultimately became known as Leḥi (Fighters for the Freedom of Israel).

Fighting For Israel’s Freedom

In Leḥi, Yitzḥak chose the name “Michael” as his nom de guerre, after the Irish Republican Army leader Michael Collins, who he had admired for his courage in fighting the British Empire.

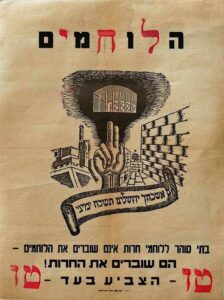

The Sternists of Leḥi declared the British presence in Palestine illegal and launched an urban guerrilla war to liberate the country from foreign rule. But the British were experienced in putting down native uprisings – especially uprisings with minimal public support. The majority of Palestine’s Jewish community didn’t understand what the Sternists were fighting for and hoped that the British would ultimately facilitate the creation of a Jewish state. The Zionist movement threw its support behind the British war effort against Germany and called on the Jewish youth to enlist in the British military.

The Sternists, by contrast, disassociated themselves from Zionism and claimed that it would be an act of idolatry for Jews to assist the British war effort without an agreement to fulfill an actual Jewish interest (mass rescue of Jews from Europe, open immigration to Palestine, a guarantee of statehood following the war).

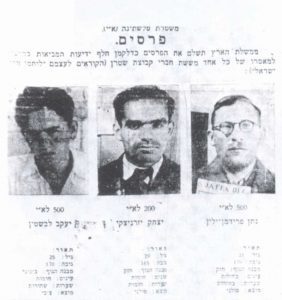

The British regime hunted down the Sternists, killing and imprisoning most of the Leḥi leadership. Michael was arrested in December 1941. After brief stints in the Yaffo and Akko prisons, he was interned in the Mitzra detention camp. It was there that he received Yair’s letter urging all incarcerated Sternists to escape.

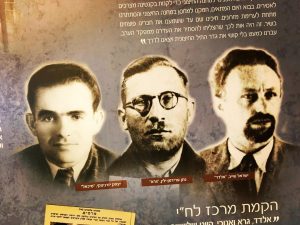

In February 1942, Yair was assassinated – shot dead while handcuffed by British detectives in Tel Aviv. The underground was decimated. But Michael was determined to carry on the fight. In September of that year, he escaped from Mitzra and began to rebuild Leḥi with Natan Yellin-Mor (Gera) and Dr. Israel Sheib (Eldad). The three comprised the “center” of the Leḥi underground. Gera was the political leader, Eldad the ideologue and Michael the operations commander.

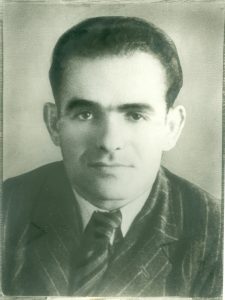

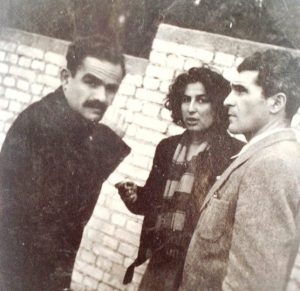

Michael got to work rebuilding Leḥi from the ruins, fighter by fighter, action by action. At this time he disguised himself as the bearded Rabbi Shamir, hiding in the shadows of Tel Aviv. He established rules of secrecy and anonymity for the underground, in order to prevent the British from destroying the movement again. He became close with his underground liaison, Shulamit, and the two eventually married and began a family.

Once the British were defeated and the State of Israel declared in 1948, Gera credited Shamir’s “will and cruelty” with helping to raise Leḥi from the ashes. In his memoirs, Eldad recalls that Michael had a tendency to immerse himself in, and micromanage, any subject or mission he took upon himself.

It is permitted to liberate a people even against its will, or against the will of the majority. When we fought for freedom, for the establishment of a Jewish state, we didn’t send a questionnaire to the Jewish nation asking if it wanted a Jewish state.

While rebuilding the underground, Michael insisted on personally interviewing nearly every recruit. Eldad recalls that this was important for Leḥi at that stage of rebirth but that this trait would later slow the movement down when the number of potential fighters grew.

In 1944, the Etzel, now under the command of Menaḥem Begin, joined the Sternists in their fight against the British regime in Palestine. While on the surface, the two movements appeared to be waging the same struggle, there still existed deep ideological differences between them. The Etzel fought against the oppressive British regime in an attempt to pressure London into adopting more pro-Jewish policies. Leḥi, by contrast, fought against the foreign regime in an effort to force the British to leave Palestine altogether. For the Sternists, the war was against imperialism, which ultimately led to demonstrations of solidarity from other progressive movements and oppressed peoples throughout the world.

During this time, Leḥi developed a political outlook that applied Marxist principles to the Jewish people’s struggle for liberation. The underground identified and targeted major British economic interests in Palestine, in order to make the price of occupation more expensive than the benefits of exploitation. One such example was the Haifa oil refinery, which the Sternists blew up on March 31, 1947. A blaze lit up the night sky for three weeks and it was only half a year before Britain announced it would withdraw from the country.

The Sternists also formulated an impressive foreign policy, the “neutralization of the Middle East,” calling for the unity of all Semitic peoples and the removal of foreign actors and imperialists from the region. The group sent dozens of representatives abroad in order to establish diplomatic branches for the movement and to initiate relations with leftist governments, institutions and activists throughout the world.

In the summer of 1946, Michael was caught during a four-day curfew and dragnet spread by the British over Tel Aviv. A policeman saw beyond his beard and ḥaredi suit and recognized the freedom fighter by his bushy eyebrows. Michael was locked up in the Jerusalem prison, in solitary confinement, but was soon put on a plane for a detention camp in Eritrea.

I don’t recognize or see the boundaries between the personal and impersonal; you might say, everything is personal, one whole, one tome with different chapters: Love of homeland and love of a precious beloved wife; missing one’s brothers, the strong sons of the homeland, and missing one’s sweet, cute son, flesh of my flesh. The boundaries are blurred, everything is beloved and precious, so attractive and so missed.

In prison, Michael met a Vietnamese prisoner, a deputy of Ho Chi Minh, who introduced Shamir to the writings of Mao Zedong. In later life, he would often call Mao a political and military genius, and line his bookshelf with the Chinese revolutionary’s writings. Sternist ideology has been compared to early Maoist tendencies on the left in that it casts the guerrilla fighter as the revolutionary agent and applies Marxist teachings to the unique context of the Jewish people victimized by foreign imperialism.

Michael escaped the detention camp in January 1947 but wasn’t able to immediately return home. As the struggle for freedom was intensifying, the British announced on September 27, 1947, that they would retreat from the country and hand responsibility for Palestine over to the newly formed United Nations.

Following the November 29, 1947 publication of UN General Assembly Resolution 181, calling for the partition of Palestine into two separate states, the Sternists published a declaration opposing the resolution: “The Freedom Fighters of Israel will continue to fight for the unity of the land with the proper tactics for each time and place.”

In late 1947, a new Leḥi daily, HaMivrak, began to appear. Under the headline, “Our Vision for a Just State,” the Leḥi leadership called for a socialist orientation, expanding on views previously expressed in HaMaas. In this essay, the Sternists called for equal opportunity for every child, universal education, and a state of justice and equality.

It was only after the British withdrew from Palestine and the State of Israel was declared, that Michael was able to return home – a free man in his land.

Michael, now Yitzḥak Shamir, joined his Leḥi comrades in creating the Fighters party to compete in the new Jewish state’s first parliamentary elections. The party called for the entire Land of Israel under Jewish sovereignty, equality for Arabs and other non-Jewish populations, a planned economy organized according to Marxist principles, opposition to the colonialist policies of the British Mandate legislation – most notably the defense emergency regulations – being incorporated into the State of Israel’s legal system, regional neutrality in the Cold War and a united front with the other Semitic peoples to protect the Middle East from the designs of imperialist powers.

The party, which was meant to further the Jewish liberation struggle, received only one parliamentary mandate in the first Knesset. It was represented by Yellin-Mor but dissolved before being able to compete in further elections.

Shamir’s Public Service

After a brief stint in business, Yitzḥak Shamir was recruited into the Mossad and served Israel in capacities that might never become public. He mostly worked in Europe, planning operations against Nazi war criminals and German scientists in Egypt. After retiring from the Mossad, he became active as an Israeli civilian in the struggle to free Jews trapped in the Soviet Union.

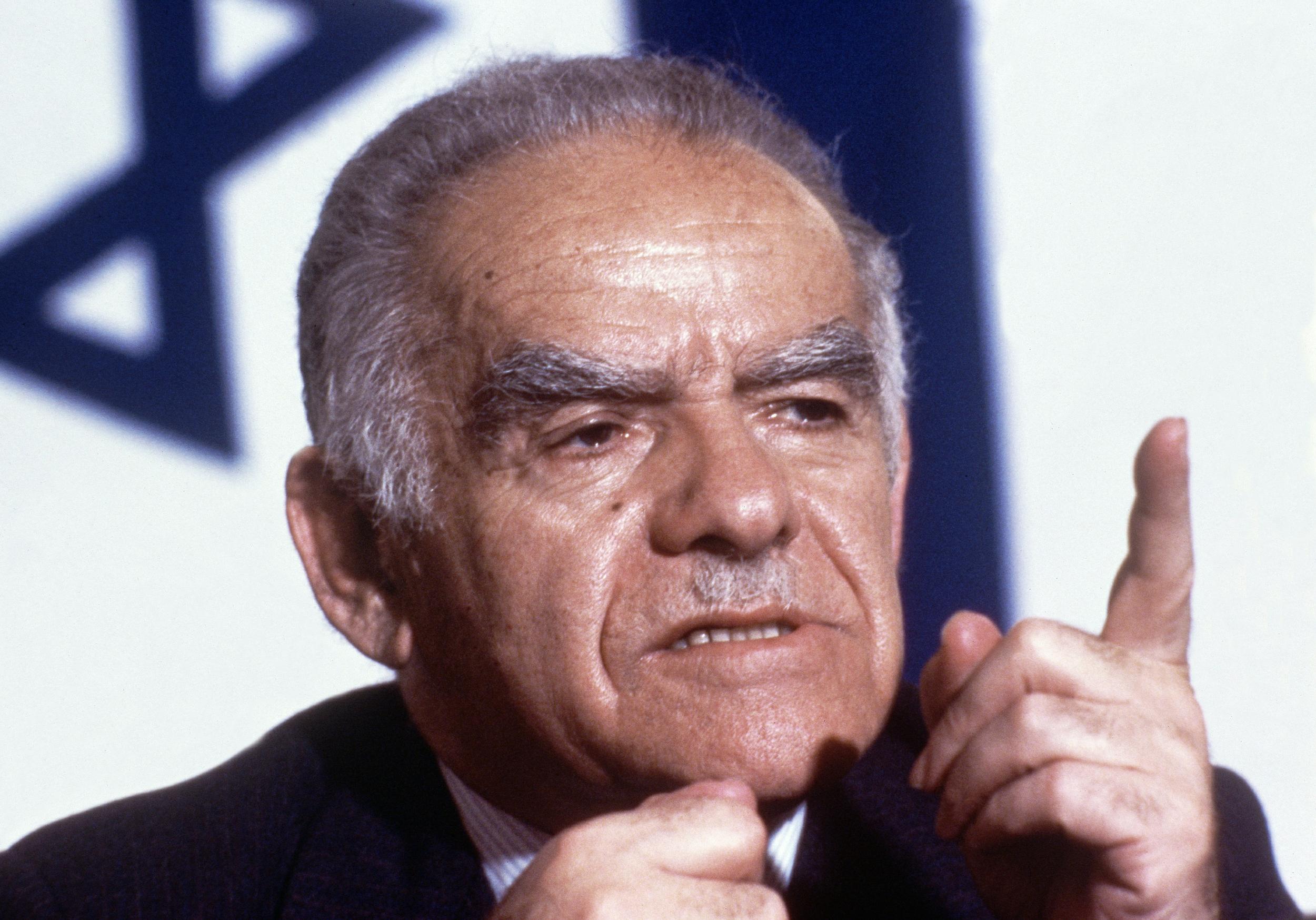

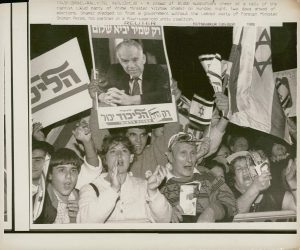

In 1973, Yitzḥak Shamir was recruited into the Likud party by former Etzel leader Menaḥem Begin. When Begin became prime minister in 1977, Shamir became speaker of the Knesset. He displayed his independence during the Begin years, opposing the surrender of the Sinai peninsula to Egypt and abstaining in the votes on the Camp David accords.

In 1980, Shamir replaced Moshe Dayan as foreign minister and when Begin abruptly retired from public life in 1983, he became Israel’s seventh prime minister. An advocate of quiet diplomacy, he helped re-establish the first links with African countries that had broken ties with Israel after the 1973 Yom Kippur War. He also saw Israel’s increasing military dependency on the United States as dangerous and attempted to diversify Jerusalem’s alliances by pivoting towards the Soviet Union.

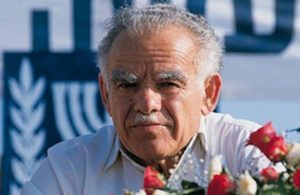

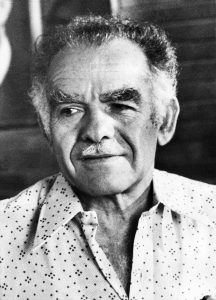

Shamir served as prime minister from 1983-84 and 1986-92, leading his party to electoral victories twice, despite lacking much of the charisma that characterizes most modern political leaders. Barely over five feet tall and built like a block of granite, he projected an image of uncompromising inner steel in the face of international hostility and pressure for Israel to relinquish land. A large percentage of the Israeli electorate trusted him to protect the nation and even those who disagreed with his principles couldn’t help but be impressed with his selfless and single-minded commitment to those principles.

As head of state, Shamir made it his mission to protect the Land of Israel and fill her with Jews, bringing his exiled brothers and sisters home from Ethiopia and the former Soviet Union. When pressured by Washington to stop building new Jewish communities in the West Bank and Gaza regions, he stood his ground and refused to allow foreign powers to dictate Jewish policies in Eretz Yisrael. The Israeli media nicknamed Shamir “Mr. No” in reference to his refusal to submit to American demands to surrender territory.

Exasperated with his resistance to Washington’s interests in the Middle East, US President George H.W. Bush and Secretary of State James Baker interfered in Israel’s political system to oust Shamir from office, hoping to replace him with the more cooperative Shimon Peres (the Americans successfully took down Shamir but Peres lost the Labor party primary to Yitzḥak Rabin prior to elections).

To date, Yitzḥak Shamir is without a doubt the strongest and most loyal national leader the State of Israel has ever had. He exemplified an inner strength and sense of responsibility to Jewish history sorely lacking from Israel’s current political leadership. As part of commemorating Michael’s yom p’tira, we at Vision Magazine urge readers to honor his legacy by helping the Vision movement to inspire the next generation with that same sense of responsibility for advancing Jewish history.

If history remembers me at all, in any way, I hope it will be as a man who loved the Land of Israel and watched over it in every way he could, all his life.