Parshat Behar opens with the laws of Shmita, a unique set of commandments that lay out a radical vision for socio-economic justice in a Hebrew state.

Addressing the question of why the Torah specifically notes that these commandments were given at Sinai, Rashi then quotes a midrash that explains Shmita to serve as an archetype for all the laws that were given over to Moshe in detail, and not just in generality.

The Rambam similarly highlights this aspect of the transmission of the Torah, opening the introduction to his great halakhic compendium, the Mishnah Torah, with the line, “The mitzvot given to Moshe at Mount Sinai were all given together with their explanations,” adding that the explanation is the Oral Torah, which is inseparable from the Written Torah.

Over the centuries, various sects have arisen from within the people of Israel that have challenged this central pillar of Hebrew thought, believing that the Written Torah could be understandable on its own, without the oral tradition passed down from master to student.

The Boethusians, the Sadducees, and even the later Karaites have largely disappeared from history. But one such group has been far more resilient – the Minim, who grew into what we know today as Christianity.

From their novel interpretations of the messianic prophecies that they use to justify their idolatry, to their pick-and-choose attitude towards the commandments on the basis of Church father (or personal) interpretation, it’s clear that the rejection of the Oral Torah is central to Christian theology.

During the centuries of Christian hegemony in Europe, it was not enough for the Church to teach its own followers to disregard the Oral Torah.

There were also repeated campaigns to turn Jews away from the tradition, in the form of public debates, censorship, and the burning of Jewish texts. While such events were common across Europe, one of the most striking was in France in the 13th century. In the year 5000 (1240 according to the Christian calendar), Pope Gregory IX and King Louis IX of France forced four of the greatest rabbis of the time, members of the school of the Tosafists, to defend the Talmud in a show trial against Nicholas Donin, a Jewish convert to Catholicism. Donin had been excommunicated by one of these rabbis, Rabbi Yeḥiel of Paris, fifteen years earlier for Karaitism.

In the course of the debate, the rabbis were forced to make their defense within the theological framework of Christianity, and were forbidden from disputing any tenets of Christian belief as part of their arguments.

King Louis unsurprisingly gave a “guilty” verdict and ordered that 24 wagonloads of Talmudic manuscripts and commentaries be burned, a sentence that was carried out in the public square next to the Notre Dame Cathedral two years later. This rampant destruction of texts recording the Oral Torah, centuries before the invention of the printing press, reveals the deep animosity for the Jewish tradition that lies at the heart of Christian theology.

But what does all of this have to do with Shmita?

One of the most common religious arguments against Jews coming on aliya to Israel is based on the Tosafot on Ketubot 110b, which brings an opinion in the name of Rabbeinu Ḥaim ben Ḥananel HaKohen that: “today, it is not a commandment to live in the land of Israel, as there are several commandments that are dependent upon the land – and several punishments – that we are not able to be careful about and to be cognizant of.”

Among these commandments, Shmita stands out as one of the most difficult to observe, since it is a far more radical approach to agriculture and economic justice than simply leaving the corner of your fields ungathered, and leaving stalks that were dropped during harvest. At face value, this is a clear cut religious argument against making aliya.

But the historic context around the compilation of the Tosafot and its printing in the Talmud are essential to understanding this argument.

The Tosafot printed in Ketubot are those compiled by Rabbi Eliezer of Tuch, who edited the earlier compilations of Rabbi Shimshon of Shans and Rabbis Moshe, Shmuel, and Yitzḥak of Evera. Both the Tosafot of Evera and the Tosafot of Tuch were edited in the aftermath of the burning of the Talmud, which destroyed a great deal of the Talmudic literature available to these compilers, and the bulk of what was preserved from the central yeshivot in Paris was preserved orally, by memory, by the students who learned there.

Rabbi Meir of Rotenburg, an eyewitness to the burning of the Talmud and the chief student of the disputant Rabbi Yeḥiel of Paris in his repsonsa, number 199, makes no mention of this ruling, nor does his student, Rabbeinu Asher ben Yeḥiel (the Rosh), both presenting the ruling of the Talmud, that Jews are obligated to live in the land of Israel, as authoritative in their times.

Another student of Rabbi Meir, The Mordekhai, mentions Rabbeinu Ḥaim, but with a drastically different wording. He writes, “Rabbeinu Ḥaim wrote in a responsa that the ruling [that one can coerce their spouse to make aliya] was in their time when the roads were safe, but now that the roads are dangerous, he cannot force her, since that is comparable to leading her into a place infested with wild animals and dangerous robbers…”

From the Mordekhai’s version of Rabbeinu Ḥaim’s ruling, it’s very apparent that the commandment to return home itself hasn’t been nullified, and that difficulty in observing the mitzvot doesn’t make them obsolete, but only that the principle of self-preservation overrides one’s ability to coerce their spouse in order to perform this particular mitzvah at a specific time. But how do we know which version of Rabbeinu Ḥaim is accurate?

In his new book, Aleh Resh, Rav Yaakov Levanon brings clear evidence for the Mordekhai’s version. He references Rav Avraham Hirsh Eisenstadt, the Pitḥei Tshuva, who attributes the version in our Tosafot to the scholars of Evera (and not the earlier and more authoritative Shans) and quotes Rav Yosef di Trani’s opinion that this passage in the Tosafot was inserted by a “Talmid To’eh” – a mistaken student.

Rav Levanon also references Rav Yisrael Ashkenazi of Shklov, the Pe’at HaShulḥan, who quotes Rav Yishaya Levi Horowitz, the holy Shlah, in rejecting this opinion as a lone position that isn’t binding and doesn’t conform with the accepted halakhic position.

Beyond the widespread rabbinic rejection of this passage in the Tosafot as authoritative, Rav Levanon clarifies the expression “Talmid To’eh” used by Rabbi Yosef di Trani, is a hidden reference to Christianity, following Rashi on Brakhot 12b, who says of the first Christians that they “turn the explanations of the Torah into mistaken and idolatrous words,” and Rambam, who across the Mishneh Torah calls Christians “To’im” – the mistaken ones.

Through the burning of the Talmud, and the widespread censorship of its passages and commentaries, the Church through the ages has sought to destroy the people of Israel by detaching us from the living Torah, the Oral Torah, that makes the commandments – even the most radical and life-changing ones like Shmita – a practical living reality.

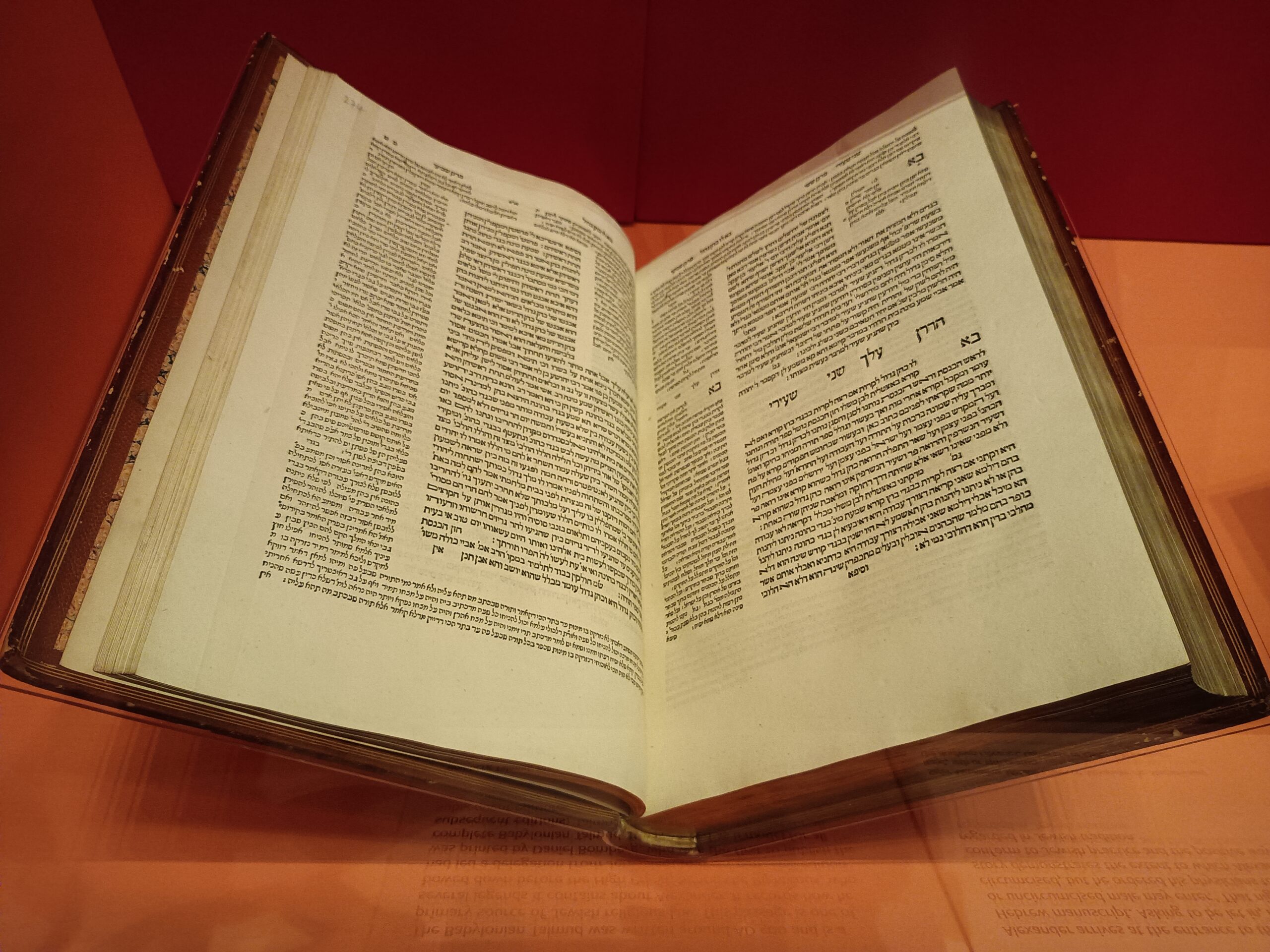

Even in more “sympathetic” times, like when Pope Leo X approved the first full printing of the Talmud by a Christian Hebraist, Daniel Bomberg, this agenda, so central to Christian theology, penetrated into our most beloved texts.

Only the light of the Oral Torah, the uninterrupted chain of transmission from master to student, has stood the test of time against their countless attempts to replace our Torah with their mistakes.