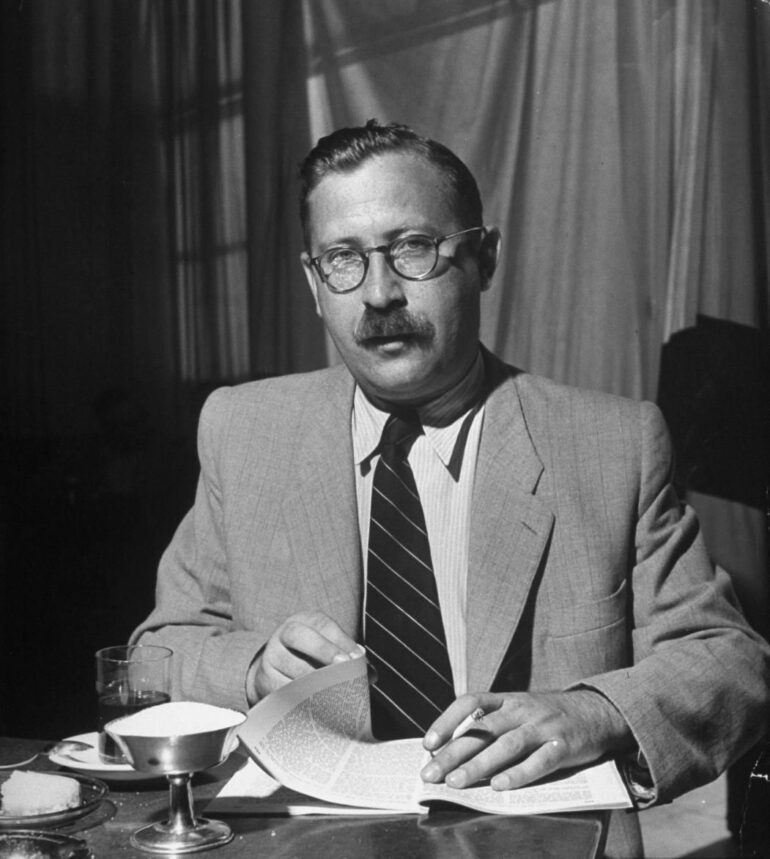

The first of Adar marks the anniversary of Natan Yellin-Mor’s passing. Yellin-Mor was the political leader of Leḥi (Fighters for the Freedom of Israel), a journalist, and a revolutionary peace activist in his later years. His complex and dynamic political thought continues to inspire a minority of thinkers while confusing most people who gain exposure to his ideas. By sharing the story of his life, however, we hope to shed light on some of his political thinking, as well as the experiences and ideas that shaped his views.

Early Life

Natan Friedman-Yellin was born in 1913 in Grodno, a mostly Jewish town that had been part of the Russian Empire at the time. His father Shmuel was a master builder who enjoyed playing the clarinet. When Natan was only a year old, World War I broke out and his father was drafted into the Russian army, never to return.

Natan’s mother Ḥanna was left with three children and no means to support them, so she moved back to her parents’ home in Lipsko, where only fourteen Jewish families lived. The place was a battlefield between empires and the terror of war made a powerful impression on young Natan, who at the age of seven received news of his father’s death.

The boy’s thirst for knowledge became evident at a very young age. At age 4, he started studying the Hebrew language and soon began learning the Tanakh, Talmud, and mathematics. Natan completed five grades in the Lipsko public school and then travelled alone back to Grodno to continue his studies at the Tarbut Hebrew gymnasium. Grodno was a bustling Jewish community at the time, where many Torah institutions and ideological movements – both Zionist & Marxist – flourished. It was in this environment that Natan acquired his love for writing.

Betar

In Grodno, Natan joined Z’ev Jabotinsky’s Revisionist Zionist Betar youth movement. Occupying the right wing of the Zionist political spectrum, Betar emphasized honor and a militant nationalism that appealed to young Jews in eastern Europe who had experienced anti-Semitic violence and frequent intimidation from gentile neighbors.

Two events influenced Natan around this time. The first was the atmosphere of Jewish nationalism at the gymnasium, which he later said he experienced as if it were a piece of Eretz Yisrael. The Zionist youth movements, especially Betar, were very popular at the school and most students were members.

The second influence was the heroic narratives of Polish Romance literature. The poetry of Juliusz Słowacki and Adam Bernard Mickiewicz, as well as the novels of Henryk Sienkiewicz, inspired young Natan.

In 1933, after completing his studies, Natan moved to Warsaw and assumed responsibility over all Betar branches throughout Poland. He eventually became an officer in the movement and worked closely with Jabotinsky and the young Menaḥem Begin. He also came into contact with the revolutionary Hebrew poet Uri Zvi Greenberg and began to be influenced by ideas beyond the intellectual boundaries of Revisionist Zionism.

In 1935, Natan aced the entrance exams to Warsaw Polytechnic’s structural engineering program. But aliya to Eretz Yisrael was always on his mind. He aspired to work as a structural engineer in Palestine, without connection to party politics. He was becoming increasingly disillusioned with Jabotinsky and the Revisionist movement, realizing that Betar would never become the revolutionary Jewish liberation movement he desired. Despite the fact that Britain ruled Palestine and set limits on Jewish repatriation, Jabotinsky refused to entertain the notion of an armed anti-British struggle.

Yair

In the summer of 1937, Avraham Stavsky introduced Natan to Avraham Stern, better known as “Yair.” Yair was a member of the Etzel (National Military Organization) high command and was organizing secret cells within Betar that would receive military training for an eventual war to free Palestine from British rule.

Yair convinced Natan to assist his clandestine work, explaining that in Eretz Yisrael, the Hebrew liberation movement was forming to fight the British occupier and free the country from foreign rule. Tens of thousands of young adults had to be armed and trained, then brought to Palestine for a war of liberation.

Natan later wrote about this period of his life in the book Sh’not B’Terem (In the Years Before), describing that after his initial meeting with Yair, he no longer felt like the same man. From that time on, he would dedicate his life to the Hebrew liberation struggle.

Natan passionately threw himself into his work. He traveled throughout Poland, meeting youth and spreading Yair’s vision. In every town, he created another cell. Many of the youngsters he organized would eventually make aliya to Palestine and participate in the underground war to free the country from British rule.

With Yair’s encouragement, Natan and his friend Shmuel Merlin created a Yiddish language Etzel newspaper in Poland, called Di Tat. With Natan as its editor, Di Tat became a daily, detailing events in Palestine and the activities of the Etzel. The publication constantly warned of the impending destruction of the Jewish communities in Europe, attacking both Zionist and non-Zionist Jewish newspapers that had attempted to lull their readers into a false sense of security. The final edition of the newspaper was August 25, 1939 – less than a week before World War II broke out.

As the war got underway, Natan married Frieda Morin, and the two decided to leave Warsaw for Palestine. Together with the Begins (Aliza and Menaḥem) and the Sheibs (Batya and Israel), they took the train to the Ukrainian city of Lviv, then continued by wagon and foot, fleeing the German blitzkrieg, all the way to Vilnius in Lithuania, where hundreds of refugees from Betar and the Etzel cells were concentrating.

While many Revisionists saw an obligation to remain in Europe to defend Jewish communities and organize anti-German resistance activities, the Sternists comprising the Etzel cells viewed the central fight as being the struggle to free Palestine from Britain and establish a Hebrew state. After a year in Lithuania, Natan and Frieda received exit visas from the Soviet authorities and they departed to Istanbul. From there, by way of Syria and Lebanon, the newlyweds reached Eretz Yisrael on January 8, 1941.

Leḥi

Upon arrival in Palestine, Natan joined the Sternists without hesitation and became Yair’s trusted advisor for several months. Yair and a small band of dedicated followers had broken away from the Etzel, which had accepted Jabotinsky’s leadership and agreed to a ceasefire with Britain. Now under Revisionist control, the Etzel called on its members to enlist in the British army.

The Sternists, by contrast, had declared war on the British and claimed that it would be an act of idolatry for Jews to assist the British war effort without an agreement to fulfill an actual Jewish objective (mass rescue of Jews from Europe, open immigration to Palestine, a guarantee of statehood following the war).

Natan became the editor the underground newspaper BaMaḥteret. He chose the nom de guerre “Gera” after the Biblical assassin Ehud ben-Gera, while his wife Frieda became known as “Efrat.”

Yair sent Gera on an important political mission, to travel to the Balkans and encourage governments there to send their Jewish populations to Palestine. Gera set out for Syria as an engineer working for a Jerusalem contractor building airfields for the British Royal Air Force near the Turkish border. From there, he had intended to continue to the Balkans. But one day, when he returned to his room after work, he was arrested by officers of the British Criminal Investigation Department (the British had arrested Efrat in Palestine and found Gera’s Syria address on a note in her purse).

Gera was transferred first to Aleppo and then, via Beirut, to Haifa and then Jaffa. After many interrogations, he was sent to the Acre prison and then to the Mizra detention camp.

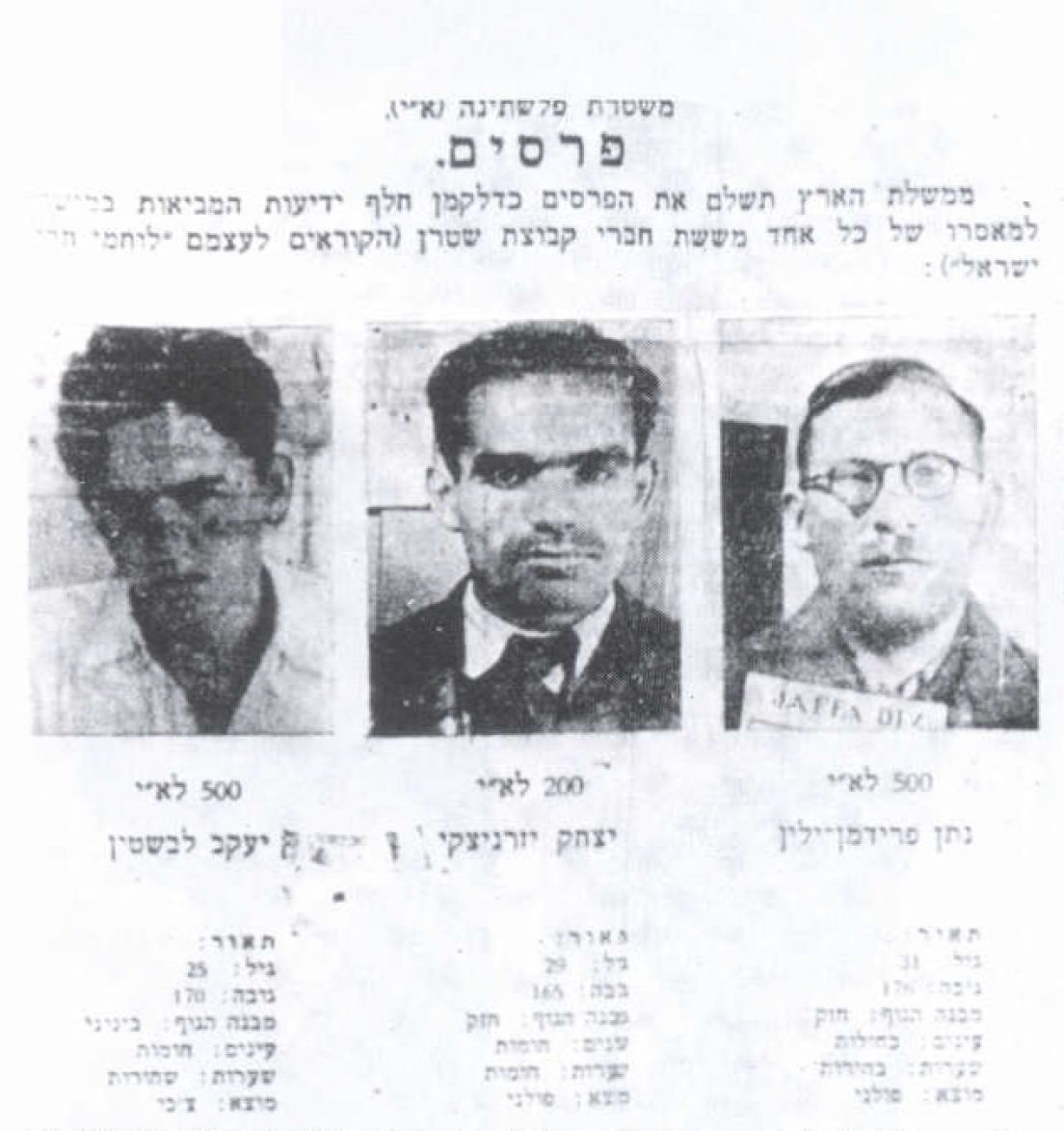

The murder of his friends Avraham Amper and Zelig Jacques before his capture, compounded by the assassination of Yair a few days after his imprisonment, devastated Gera. But he believed that the Jewish war of liberation must continue until the foreign ruler would be forced from the homeland. Together with some surviving Sternists in and out of prison, Gera began to reorganize the movement into Leḥi (Fighters for the Freedom of Israel).

Gera never accepted imprisonment. From the moment of his arrival, he planned his escape. After Yitzḥak Shamir, known as “Michael” in the underground, escaped from Mizra in 1942, Gera became the senior prisoner among the Sternist inmates. While Michael rebuilt the underground on the outside, Gera put his literary acumen to good use on the inside. “Tearing Down the Prison Walls” was published in the revived BaMaḥteret and served to raise the spirits of the underground fighters.

In the essay, Gera explained that detention was a dangerous weapon in the enemy’s hands, serving to break the spirits of the freedom fighters and take them off the battlefield. The prisons had to be destroyed so no fighter could allow himself to be taken captive. The new directives were for every Leḥi fighter to carry a weapon at all times. And to immediately use that weapon if stopped by British authorities. Either the underground would destroy the prisons or the prisons would destroy the underground.

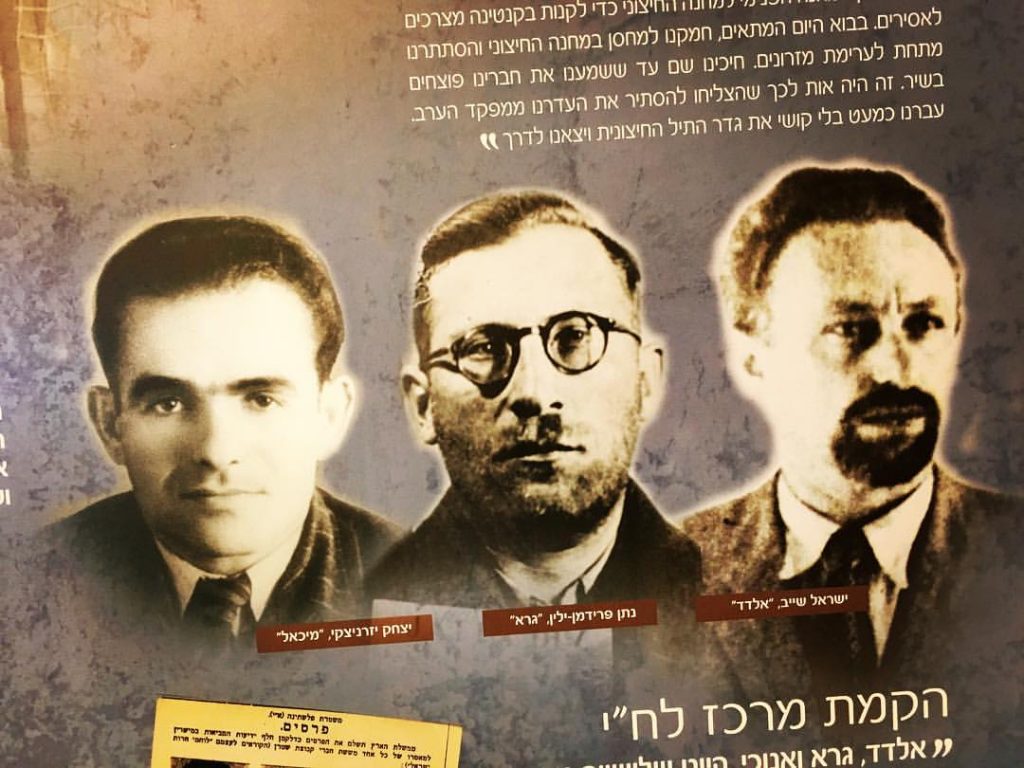

On November 1, 1943, Gera and nineteen of his comrades executed a daring escape from the Latrun detention camp through a 75-meter tunnel they had dug. Once free, Gera convened the Leḥi center, together with Michael and Dr. Israel Sheib, known in the underground as “Eldad.” Eldad formulated the underground’s ideology and Michael was responsible for the group’s operations. Gera was the political leader.

Hunted by the CID, Gera took the pseudonym Asher Wilensky and constantly kept moving from place to place every few days. While Michael and Eldad were imprisoned, he took on additional responsibilities. In 1943, he wrote to Eldad that “We must stress with great emphasis that we are not a Zionist movement. Zionism is empty of all content and no longer compels us forward to accomplish anything more. We are not a Zionist option and it is not our duty to bring this or that party back to the proper path. We are the Hebrew liberation movement in the Land of Israel. For us, Zionism is dead and we no longer wish to busy ourselves trying to revive it or anything else of its kind.”

In the fall of 1944, the official Zionist Hagana militia initiated the Saison – hunting down Etzel and Leḥi fighters on behalf of the British regime. Gera met with Hagana commander Eliyahu Golomb, placed a pistol on the table, and threatened to assassinate members of the Zionist leadership if any of his fighters were touched.

From then on, the Saison targeted only Etzel fighters, whose commander Menaḥem Begin had made clear his determination to avoid violence between Jews at any price.

In early September 1945, after the Saison had ended, Gera met with Israel Galili, Moshe Sneh and Begin to coordinate anti-British activities. For the next nine months, there existed a united Hebrew Resistance Movement comprising the Hagana, Etzel, and Leḥi. But this effort was short lived as the Zionist politicians directing the Hagana had no real interest in fighting the British. Even the Etzel spoke of the British rulers as the “oppressive regime” and fought for the sake of improving British policies. Only Leḥi, far more advanced in its political thinking, referred to the British as the “foreign regime.”

Gera became the editor-in-chief of the Sternist magazine, HaMaas. After Michael was arrested in the summer of 1946 and exiled to a detention camp in Africa, Gera took charge of Leḥi‘s organizational direction. He loosened Michael’s centralization of operations, allowing cells throughout Palestine to plan and execute their own anti-British attacks.

Under Gera’s leadership, Leḥi developed a sophisticated political outlook that applied Marxist principles to the Jewish people and its struggle for liberation. The underground identified and targeted major British economic interests in Palestine, in order to make the price of occupation more expensive than the benefits of exploitation. One such example was the Haifa oil refinery, which the Sternists blew up on March 31, 1947. A blaze lit up the night sky for three weeks and it was only half a year later that Britain announced it would withdraw from the country.

Gera also formulated an impressive Sternist foreign policy, the “neutralization of the Middle East,” calling for the unity of all Semitic peoples and the removal of foreign actors and imperialists from the region. He sent dozens of representatives abroad in order to establish diplomatic branches for the movement and to initiate relations with leftist governments, institutions, and activists throughout the world.

As the struggle for freedom was intensifying in 1947, the British announced they would retreat from the country and handed responsibility for Palestine over to the newly formed United Nations.

Following the November 29, 1947 publication of UN General Assembly Resolution 181, calling for the partition of Palestine into two separate states, Gera and Eldad published a declaration opposing the resolution: “The Freedom Fighters of Israel will continue to fight for the unity of the land with the proper tactics for each time and place.”

As for Palestine’s Arab population, Gera stated that “the national interests of the Hebrew people and the essential interests of the inhabitants of the land, without any distinction of national origin, religion or race, dovetail with one another.”

In late 1947, a new Leḥi daily, HaMivrak, began to appear. Under the headline, “Our Vision for a Just State,” Gera called for a socialist society, expanding on views he had previously expressed in HaMaas. In this essay, he called for equal opportunity for every child, universal education, and a state of justice and equality.

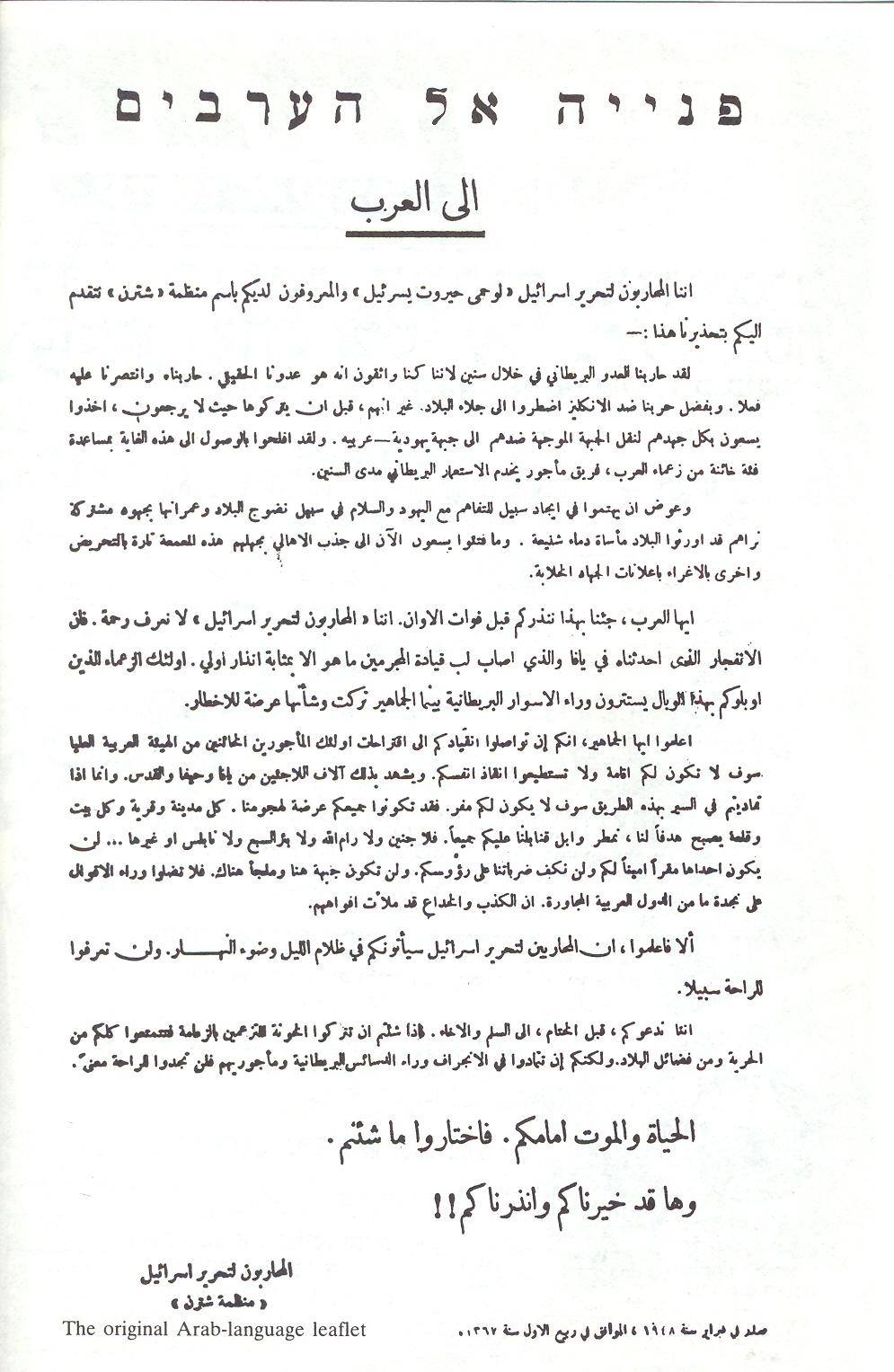

The Leḥi center, under Gera’s leadership, published Arabic-language pamphlets calling for peace, brotherhood, and a shared struggle against the imperialists victimizing both populations and forcing them into needless conflict. He believed that the Jewish-Arab fighting that had broken out following the publication of the UN partition plan would not escalate but would subside once the British fully withdrew from the country. He hadn’t counted on the British inciting and leading an invasion of neighboring Arab armies into Palestine following their withdrawal. The result was a bitter war that resulted in a catastrophic Palestinian refugee crisis, as well as Egyptian rule in Gaza and Jordanian rule over Jerusalem and the West Bank.

We of Lehi, known to you as the “Stern Gang,” warn you:

We have fought the British enemy for years, because we were convinced that they were the true foe and we overcame them… But prior to their leaving they have tried to turn the international front into a Jewish-Arab one. They have succeeded in doing so through the help of traitorous gangs led by mercenary leaders who have served British imperialism for years.

Instead of trying to find a way to understanding with the Jews in peace so as to improve this country jointly, we see how they are bringing havoc on this land in a despicable bloodletting. And now they attempt to exploit the ignorance of the masses and to draw them in on the one hand by frenzied propaganda and on the other by baseless jihad.

O Arabs! We warn you before its too late. We of Lehi will know no mercy. The explosion at Jaffa’s Saariya was the first warning. Those criminal leaders killed brought upon you these troubles, hid behind British skirts and the masses are left on their own.

Know o Arab community! If you continue to heed the advice of the hired traitors of the Higher Arab Committee, you will not establish anything nor will you save yourselves. Proof of this are in the thousands of refugees from Jaffa, Haifa and Jerusalem. If you continue you’ll find no asylum; all of you will be a target of attacks. We will bomb your towns and villages. Neither Jenin, Ramallah, B’er Sheva nor Sh’chem will serve you as shelter… Don’t follow blindly the talk of reinforcements from the Arab neighboring states for falsehood has overflowed.

Therefore know that Lehi will come to you at night and during the day and you will know no rest.

At this last moment we call to you for peace and solidarity. If you quit your treasonous leaders you will benefit from freedom and the blessing of this land. But if you follow the evil designs of the British and their hirelings, they will not save you.

Before you are life and death. The choice is yours.

We have given you the alternative and warned you.

Approaching Israel’s Declaration of Independence, the Leḥi center decided to demobilize its fighters so they could enlist in the new IDF. In Jerusalem, however, Leḥi remained an independent force that continued to fight for the city’s liberation and inclusion in the Jewish state.

On September 17, 1948, the center decided to assassinate Count Folke Bernadotte, a Swedish diplomat and UN representative attempting to internationalize Jerusalem.

Following the assassination, Gera was arrested and brought before a military tribunal. He was sentenced to imprisonment for membership in an illegal organization, but was later released under a general amnesty.

The Fighters Party

In order to participate in elections to Israel’s first Knesset, the Sternists formed the Fighters party. Led by Gera and Michael, the Fighters party identified its ideology as revolutionary socialist and included both Jewish and Arab veterans from Leḥi on its list for Knesset. Although also a candidate on the list, Eldad had begun to devote his energies to building an educational movement.

The Fighters party exhibited a political sophistication and ideological creativity unique to Sternists that transcended Israel’s shallow left-right binary. Among its positions were:

- The entire Land of Israel under Jewish sovereignty

- Equality for Arabs and other non-Jewish populations

- A planned economy organized according to Marxist principles

- Opposition to the colonialist policies of the British Mandate legislation – most notably the defense emergency regulations – being incorporated into the State of Israel’s legal system

- Regional neutrality in the Cold War

- A united front with the other Semitic peoples to protect the Middle East from the designs of imperialist powers

The party only received 5,363 votes and Gera became its sole representative in Israel’s parliament. Two years later, the first Knesset was dissolved and the Fighters party fell apart.

Semitic Action

Absorbing his wife’s maiden name into his family name, Natan Friedman-Yellin became Natan Yellin-Mor. In 1954, he took charge of the largest private farm in the country and appeared to retire from public life. But his frustration with the fact that the young State of Israel he fought to create was aligning itself with oppressor and imperialist nations forced him to return to political activity.

In 1956, Natan Yellin-Mor created the Semitic Action movement together with comrades from Leḥi and other leftist intellectuals. Its Hebrew Manifesto was published in 1958 and contained revolutionary ideas regarding the place of the Hebrew people among the broader Semitic region, calling for a democratic state, a free socialist economy, support for anti-colonialist movements, universal education, and a binding constitution.

Semitic Action called for the creation of a regional anti-imperialist federation encompassing Israel and its neighbors. Natan Yellin-Mor and his friends lamented the fact that Israel, under the leadership of Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, had a policy of superpower patronage that aspired to serve as an outpost for imperialist interests in the Middle East rather than allow the state to indigenize into the region.In December 1960, several members of Semitic Action created the Israeli Committee for a Free Algeria, a group supportive of the FLN in the Algerian War. This was in opposition to the Israeli government’s official policy of siding with France in that conflict.

Between 1960 and 1967, Yellin-Mor published a bi-weekly by the name of Etgar, which served as an ideological forum for left-wing intellectuals seeking a peaceful solution to the Arab-Israeli conflict.

In 1969, Natan Yellin-Mor ran for Knesset as leader of the Nes party but failed to win any seats. After the 1973 Yom Kippur War, he brought messages of peace from Egyptian emissaries to Israel’s government, but these were rejected. During the 1970’s, he continued to write articles.

In 1974, Natan Yellin-Mor published his book, Freedom Fighters of Israel – Personalities, Ideas, and Adventures, in which he tells the story of Leḥi. Sh’not B’Terem describes his experiences in Poland and his journey to British-occupied Palestine during World War II. The manuscript was discovered posthumously and published in 1990.