About a month before I embarked on my summer in Israel, the United States decided to move its embassy to Jerusalem, acting through a bill passed in 1995 legally recognizing Jerusalem as the rightful capital of the State of Israel.

This move coincided with what was then thought to be the climax of protests in Gaza. I sat on my dorm room bed in Washington, DC, reading the news and the various articles attempting to predict the political backlash of the decision. As I was reading about the already numerous deaths in Gaza that day, there was a knock on my door.

I opened it to see a friend who asked if I wanted to come sit with her and the other Palestinian students on campus while they set up a memorial on the quad to mourn the fallen.

My answer was not immediate. I often still think of that moment, and of what hung in the silence.

She knows I am a Jew, that I was preparing to spend my summer in Israel. She knows as well that I am studying International Service, and that the language I chose to study is Arabic.

I know that she is Muslim and a hijabi, that she’s from the West Bank, and that she is a good friend. As a Jew, I know that we have had the experience of being closed out of our land. I can relate to feeling like a target just because of my identity.

What hung in the silence was years of conflict. Two people, conditioned to identify as coming from intrinsically dichotomous, mutually exclusive cultures. Yet what also hung in the silence was an opportunity to bridge a gap, an opportunity to empathize.

I decided to seize the opportunity and say yes.

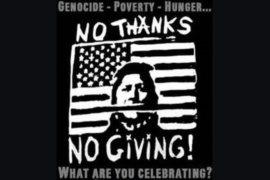

As a Diaspora Jew, and specifically a Diaspora Jew on an American college campus with an increasingly anti-Israel bias, I feel a constant struggle when it comes to Israel. People will ask me if I believe that Israel has a fundamental right to exist. People will ask me why I choose to identify with a nation that violates human rights and kills innocent Palestinians for fun. The system seems rigged to pull me away from my identity and turn me against my people. To them, a pro-Israel Jew is a blind and unwavering supporter of everything that the State of Israel does, rather than an individual with sentiments and beliefs on a spectrum.

It seems that in response, Jewish communities in the Diaspora have slipped into a defensive mindset and often fall back on the easiest reasoning to support these positions. For example, when talking to people who are highly critical of Israel, sometimes it can be easier to fall back on the Holocaust or other experiences of persecution in exile as justification for our claim to the land, when really the story starts much earlier.

Every day that I was in Israel this past summer, I learned more of the history and the stories of the peoples who have lived in that land. Every day, I added another weirdly-shaped puzzle piece to fit into the huge jigsaw that we call the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, of which I feel most people – myself included – only have the corner pieces laid out.

But where did all the pieces in the center go?

I feel that it is much easier for Jews to end up rallying against Israel as a whole when they don’t understand the full history of their people and homeland. Not necessarily the state but the people and land.

Without the middle pieces of the puzzle, it’s impossible to know that in practically every century that we were in exile, Jewish liberation movements attempted to return us to our land. It would be impossible to know that Jews never stopped fighting for the past 2,000 years to regain our independence. We are not just showing up and demanding land, as it would seem when only the corners of the puzzle are in place.

Included in the center pieces are also the Palestinian narrative and all of its complexities.

It is easy to feel, by sitting with my friend as she put out miniature Palestinian flags inscribed with the names of the fallen, that I had in some way betrayed my people. Some of my Jewish friends on campus wouldn’t acknowledge me as I sat there, some wouldn’t even turn their heads when I called out their names to come speak.

I believe that as Semites, Jews and Palestinians have more in common than not, yet the dialogue surrounding the conflict has been overwhelmingly about our differences and how incompatible our cultures are. Real cultural empathy is the ability to see, respect, and understand the differences in other cultures and realize that culture is relative: there is no overarching right or wrong when it comes to culture and identity, just similarities and differences.

As a Jew, I believe in Tikkun Olam, in repairing the world and leaving it in a better condition than it was in before I came into this life.

Tikkun Olam drives me to advocate for human rights first, far before my allegiance to a political party or organized movement. Perpetuating conflict by refusing to acknowledge similarities is neither productive nor does it align with my understanding of Jewish values.

But I must not forget that I am a Diaspora Jew and not yet an Israeli citizen. As a result, I feel a sense of illegitimacy in my opinions. I can spew whatever views I have to college-aged Americans, and they can agree or disagree with me, but a conversation with an Israeli or Palestinian is very different. Although for me the conflict has created an ideological challenge, for them it is their daily, lived reality. Israelis and Palestinians alike are living this reality while I sit in the comfort of my American life, watching the conflict unfold on screens and in print. As a Jew, I cannot deny that I am involved. Yet I also cannot deny that when speaking with people actually impacted by these realities on a daily basis, there is a degree to which my opinions are irrelevant.

I don’t think it is detrimental for an American Jew to recognize this status, and I wish more would accept this mindset. My role as a Diaspora Jew is important, but it is vital to know when our viewpoints are no longer furthering the discourse. Bringing our idealistic, romanticized views of two-state solutions and Israel’s moral army tends to be unrealistic, but this is for a plethora of reasons, including our Western educations and inability to receive reliable information from news sources or advocacy organizations. Our Westernized views of conflict and how it should be resolved are, again, relative to the West. Middle Eastern cultures are very different from Western cultures, and thus conflict must be handled in a way that is authentic to the peoples, values and cultures of the region. In short, there is no Western solution to a Middle Eastern conflict.

Being a Diaspora Jew is not easy, and – when confronted – it comes with many moral, religious, and cultural dilemmas that almost never have clear answers. It constantly challenges my own views and identity and pushes me to pursue further knowledge about my own worldview, culture, and value system, all of which are undeniably intertwined in Jewishness.

This past summer in Israel undoubtedly opened my eyes to a much larger picture and helped me to find a better place for myself in the story of my people’s return to our land and the numerous complications that have come along with that.

‘As a Jew, I believe in Tikkun Olam, in repairing the world and leaving it in a better condition than it was in before I came into this life.’

Your misinterpretation of the essential meaning of the term, rooted deeply in ancient spirituality, is at the core of all-too-many young peoples’ misguided choices and actions. Do what you want and cal, it what you want, except don’t call it Judaism. It isn’t!

Galut is not a matter of geography. Galut is a state of mind, My problem with your notion of Diaspora Judaism is that if you are at home with yourself as a Jew in one place, you are at home with yourself as a Jew everywhere. Whether we feel comfortable about it are obligated by the Ribono shel Olam to follow the path that is set for us. As appealing as Tikkun Olam sounds, it is the result of following that path and comes at the end of our prayers . It establishes the Kingdom of God, whatever that means and, for the Jew closes out Galut, wherever they might be.

Indeed, being a Jew means going from Galut to Dveykut, clinging to the Ribono shel Olam. It starts out with Mitzvot that put the world in order, yes, Tikkun Olam. It is never easy, though, it is far better to do it in the Land of Israel. In Hebrew the word Pashoot, means “simple”, but for Jews it is not as easy as it seems. So Sam, you and me and all the rest of the Jewish people work at it every day.