We are taught “V’ein kol ḥadash taḥat hashemesh” – “And there is nothing new under the sun” (Kohelet 1:9).

The assertion that there is no true novelty in this world is a striking one. In a world that seems to be constantly evolving and changing, how are we to understand the ancient wisdom of Solomon?

As a student of history, I often hear clichés such as “history often repeats itself” and “those who do not learn from history are bound to repeat it.” But in my studies of Jewish history, and even more so in my closer readings of Jewish historiography, I have seen time and time again that the idea of history as a cyclical – rather than linear – progression is deeply embedded in our national consciousness.

The Western world understands history in the framework of timelines. It has a beginning, an end, and a series of ordered events in between.

While Western historians frequently draw thematic parallels between different historic periods, and try to derive broader societal lessons from such analyses, their analyses are still deeply grounded in a fundamental understanding of history as linear.

This is especially true of the Marxist historical framework. Based around Karl Marx’s depiction of history as a series of escalating class struggles in The Communist Manifesto, this school of historiography attempts to frame historic events and developments within the context of the material conditions and dominant class struggle of the time.

An analysis of the Roman Empire’s military, for example, would highlight the roles of patricians, plebeians, and slaves in supporting and staffing that military, and the power dynamics built into that system. In general, this means that each historical era, defined by a new form of class struggle (masters and slaves, feudal lords and serfs, bourgeoisie and proletariat) receives its own vocabulary, systems of power, and ideological forces.

In the Marxist framework, these attributes are generally exclusive to each era, because they are intrinsically tied to the relevant form of class struggle, and therefore it is anachronistic and nonsensical to speak of industrial feudalism, classical colonialism, or medieval liberalism.

In contrast, the Jewish people has traditionally understood history as cyclical, as a constant repetition, not just of broad themes but of societal forces, foci of conflict, and ultimate aims.

While Hebrew historiography has tended to accept and acknowledge a general conception of spiritual advancement towards an ultimate ideal, this understanding transcends Western understandings of material and economic progress and development. This is in large part due to our primordial understanding of umot – “nations” – which are understood not just as physical groups of people, but also as driving moral spiritual forces that have animated the events of history since antiquity.

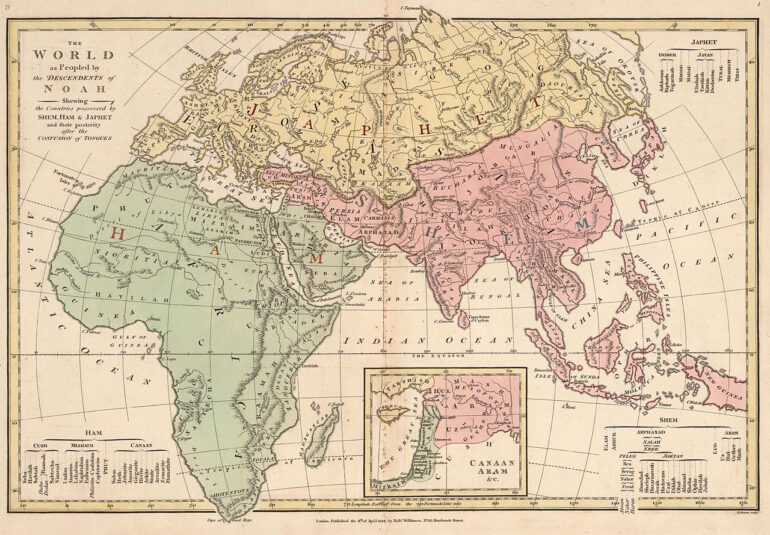

Rather than adopting the perspective of Western historians that view national identities and their accompanying mythologies and characteristics as modern social constructs, Jewish scholars have tended to classify the nations of the world in each generation as incarnations of the primordial Biblical nations based on the specific challenges and threats they pose to the Jewish people and humanity at large. While discourse around iterations of Esav, Ishmael, and Amalek is exceptionally common, there are also countless other examples.

Such perspectives have shaped Hebrew understandings of history and distinguished them considerably from traditional Western understandings.

For example, while a Marxist reading of the Jewish revolts against the Roman Empire would exclusively highlight the Roman ideal of spreading civilization, Jewish (primarily plebeian) resistance to the Emperor’s agents and their administrative programs, class conflict within Judean society at the time, and the clash over material interests used in service of each side’s aspirations, traditional Jewish histories of the period (both contemporary and ancient) primarily frame the Jewish-Roman conflict as a clash between Edom, the ideological descendants of Esav, and Israel, the ideological descendants of Yaakov.

These uprisings are seen as a repetition of Biblical tensions that remain in constant conflict throughout history.

The richness of Jewish historiography, as well as the moral and intellectual ideals it espouses, are an essential component of Israel’s historic national psyche. In the present moment, if we are to seek to emulate our ancestors, or even just to learn from their experiences, we must do so with attention to how they understood themselves, the world around them, and the generations that preceded them.